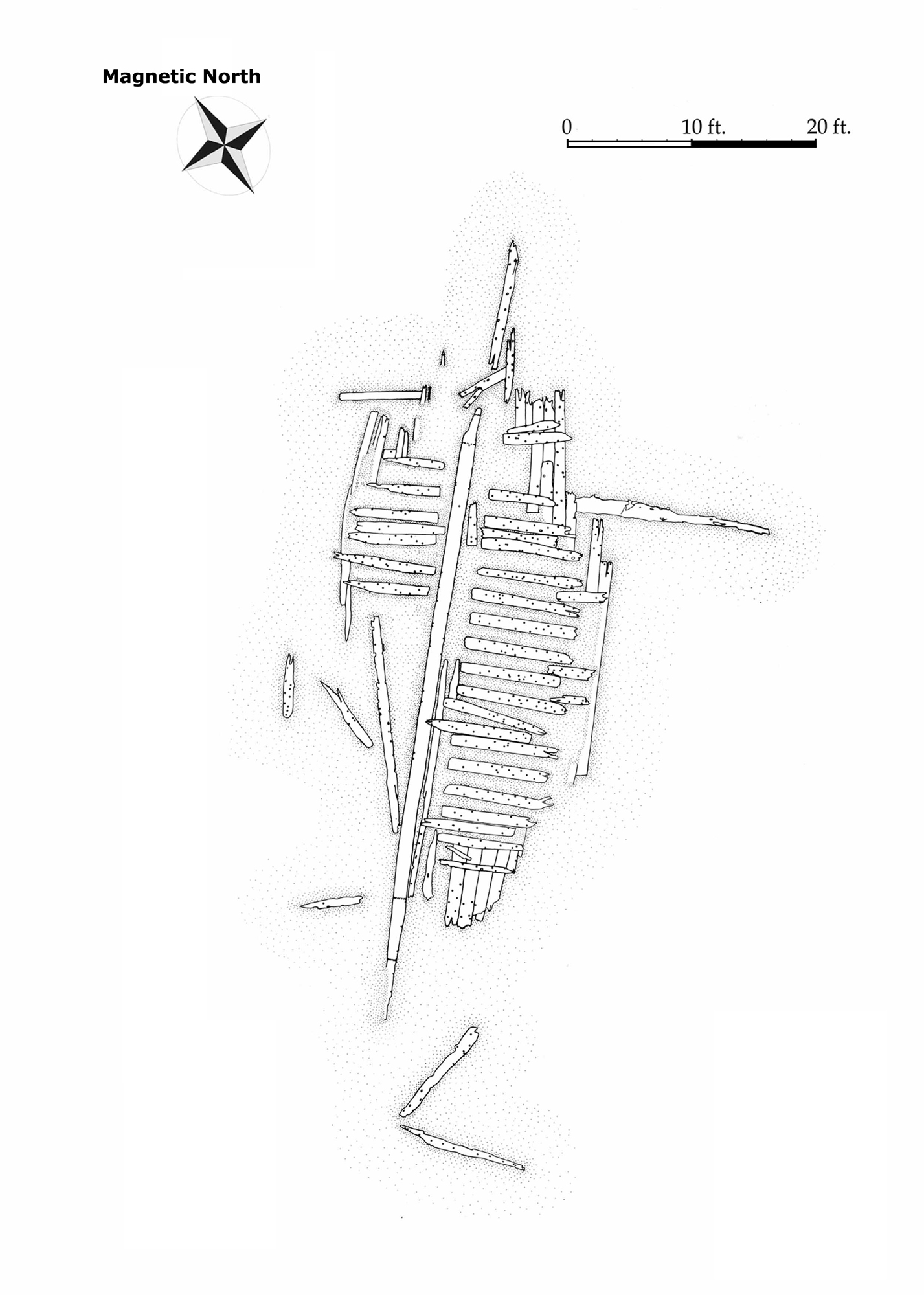

The Seal Cove Shipwreck Project, funded by the National Park Service’s Submerged Resources Center and the Institute for Maritime History, recorded archaeologically a historic wooden shipwreck on Mount Desert Island, Maine. Situated in the inter-tidal zone on Acadia National Park easement land owned by the Town of Tremont, the wreck was surveyed between July 30 and August 6, 2011. The exercise of shipwreck recording provided Park staff and volunteers with experience in documenting maritime cultural resources, and gave project personnel an opportunity to conduct community outreach highlighting the importance of preserving Maine’s maritime heritage. Project objectives were twofold. First, archaeologists would investigate and record an historic shipwreck in Seal Cove, producing a site plan (Figure 1) and report. Second, they would use the process to provide training for Park staff and volunteers in maritime archaeological methods and techniques. The project also provided an internship for a graduate student from East Carolina University’s Program in Maritime Studies. Numerous volunteers contributed to the project through mapping, drawing, photographing, researching, and writing.

The Seal Cove Shipwreck Project, funded by the National Park Service’s Submerged Resources Center and the Institute for Maritime History, recorded archaeologically a historic wooden shipwreck on Mount Desert Island, Maine. Situated in the inter-tidal zone on Acadia National Park easement land owned by the Town of Tremont, the wreck was surveyed between July 30 and August 6, 2011. The exercise of shipwreck recording provided Park staff and volunteers with experience in documenting maritime cultural resources, and gave project personnel an opportunity to conduct community outreach highlighting the importance of preserving Maine’s maritime heritage. Project objectives were twofold. First, archaeologists would investigate and record an historic shipwreck in Seal Cove, producing a site plan (Figure 1) and report. Second, they would use the process to provide training for Park staff and volunteers in maritime archaeological methods and techniques. The project also provided an internship for a graduate student from East Carolina University’s Program in Maritime Studies. Numerous volunteers contributed to the project through mapping, drawing, photographing, researching, and writing.

SITE DESCRIPTION

The Seal Cove shipwreck (ME 436-028) was reported by local informants in 2006 and put on file with the Maine Historic Archaeological Sites Inventory in July 2007 by Anthony Booth of Independent Archaeological Consulting (Price 2007; Maine Historic Preservation Commission 2007:1-2).

The Seal Cove shipwreck (ME 436-028) was reported by local informants in 2006 and put on file with the Maine Historic Archaeological Sites Inventory in July 2007 by Anthony Booth of Independent Archaeological Consulting (Price 2007; Maine Historic Preservation Commission 2007:1-2).

Wooded land meets the shore near the wreck, with exposed rock ledge at the shoreline. Rocks and boulders are scattered about the site, including two large boulders at either end of the vessel remains, and scattered rocks within the vessel structure. The rocks and boulders appear to be local. Exposed bedrock on the western side of the wreckage gives way to a mixture of mud and gravel, with a layer of fine mud covering vessel timbers. Underneath the keel, investigators encountered mud over compact clay. On the eastern side of the wreck, mud nearer the timbers transitions to a gravel and mud mixture, sorted by local hydrodynamics. The vessel rests in an inter-tidal, low energy environment, in a sheltered cove. The cove itself is noted for being well-suited for careening, a practice that carries on to today. Even in times of storm the narrow entrance does not permit rough seas to enter its shielded waters. Biologically, the wreck is home to barnacles, marine mollusks, crabs, and seaweed.

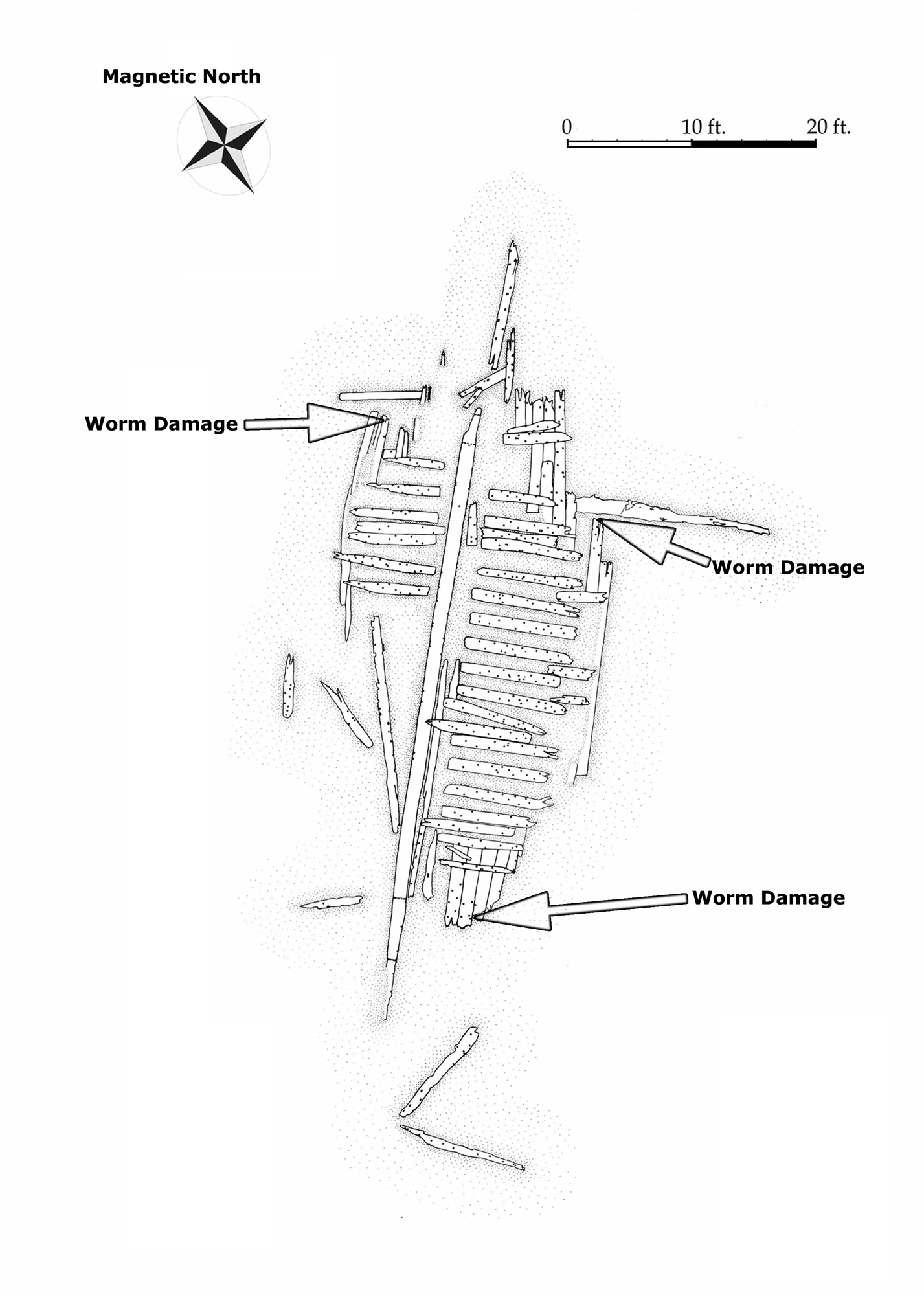

The vessel is deposited on largely flat terrain, slightly sloping downward to the east. The exposure of bedrock and boulders on the west may account for the vessel’s poorer state of preservation on that side. The hull to the west appears to have been broken by the bedrock, while on the east parts of the hull were cushioned by mud and gravel. The keel is oriented at 38° from magnetic north. The debris runs roughly along the same axis as the continuous vessel structure. Most of the vessel is missing. There is no discernible ballast, no sternpost, ceiling, or deadwood. No structure remains beyond the turn of the bilge. All of the frames stop before reaching the keel, except for F8, a lone frame hanging slightly over the keel that may represent a floor. Much of what is left is degraded, eroded, and weathered.

It is difficult to determine which end of the wreck is bow or stern, but a piece resembling stem structure is northeast of the keel. The site itself is largely continuous, with a few outlying pieces nearby that may be part of the vessel, as well as a few further away in the cove that likewise appear to be disassociated parts of the wreck. These outlying scantlings share dimensional characteristics with the vessel and also have wooden fasteners.

The remains of the vessel have been subjected to tidal submergence, alternating exposure to air and water, which has had a deleterious impact on its structural integrity. Ice damage in winter has also been a factor, as the cove is subject to freezing, while silt deposited on the wreck on the incoming tide may have helped with its preservation. This was observed during the survey; frames covered in sediment were far better preserved than exposed wood. There were no obvious signs of vandalism.

BRIEF NOTES ON THE HISTORY OF THE INTERIOR COVE

In the historic period, Seal Cove has been a locus of maritime activity since just after the Revolutionary War. American families settled on either side of Seal Cove in the 1780s (Street 1905:150). It was the site of a saw mill on maps as early as the 1790s (Peters 1795:1). The settlement grew to the extent that by the latter nineteenth century it also had a store, a post office, a boat builder, and three blacksmiths (Dodge 1871:50-55; Lapham 1886:20).

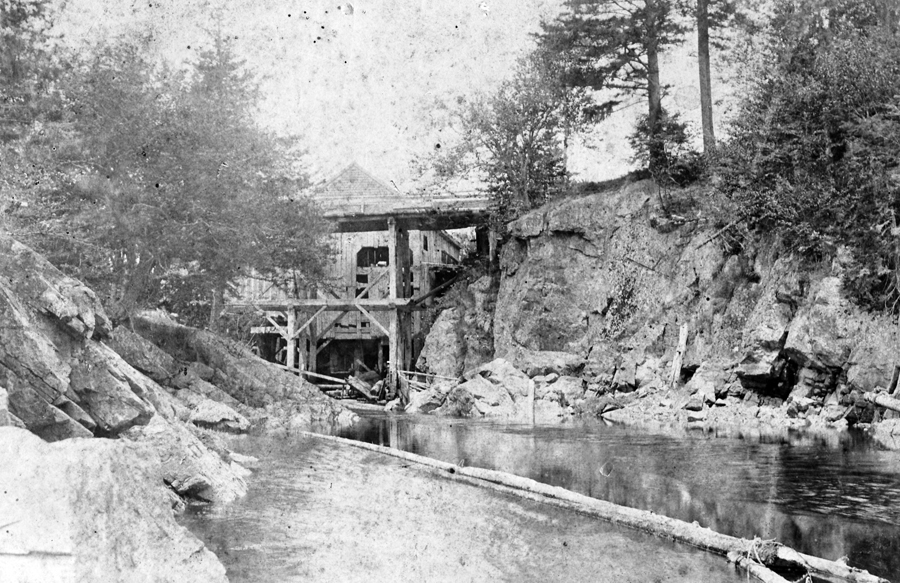

In these decades “lumber, ice, fish and granite” were the primary industries on Mount Desert Island, the saw mill contributing to the former (Street 1905:309). Historic photographs show the cove as a modest center of industry and maritime activity. One photograph features a saw mill located near where the Route 102 Bridge is today, while another shows small boats, apparently sloops (Figures 2, 3 and 4).

OUTREACH

Twenty people, with varying levels of archaeological experience, participated in an on-site informal field school in maritime archaeological site recording (Figure 5). They acquired archaeological data including vessel dimensions, scantling measurements, fastener and fastener hole diameters, drawings, and photographs.

Twenty people, with varying levels of archaeological experience, participated in an on-site informal field school in maritime archaeological site recording (Figure 5). They acquired archaeological data including vessel dimensions, scantling measurements, fastener and fastener hole diameters, drawings, and photographs.

METHODS

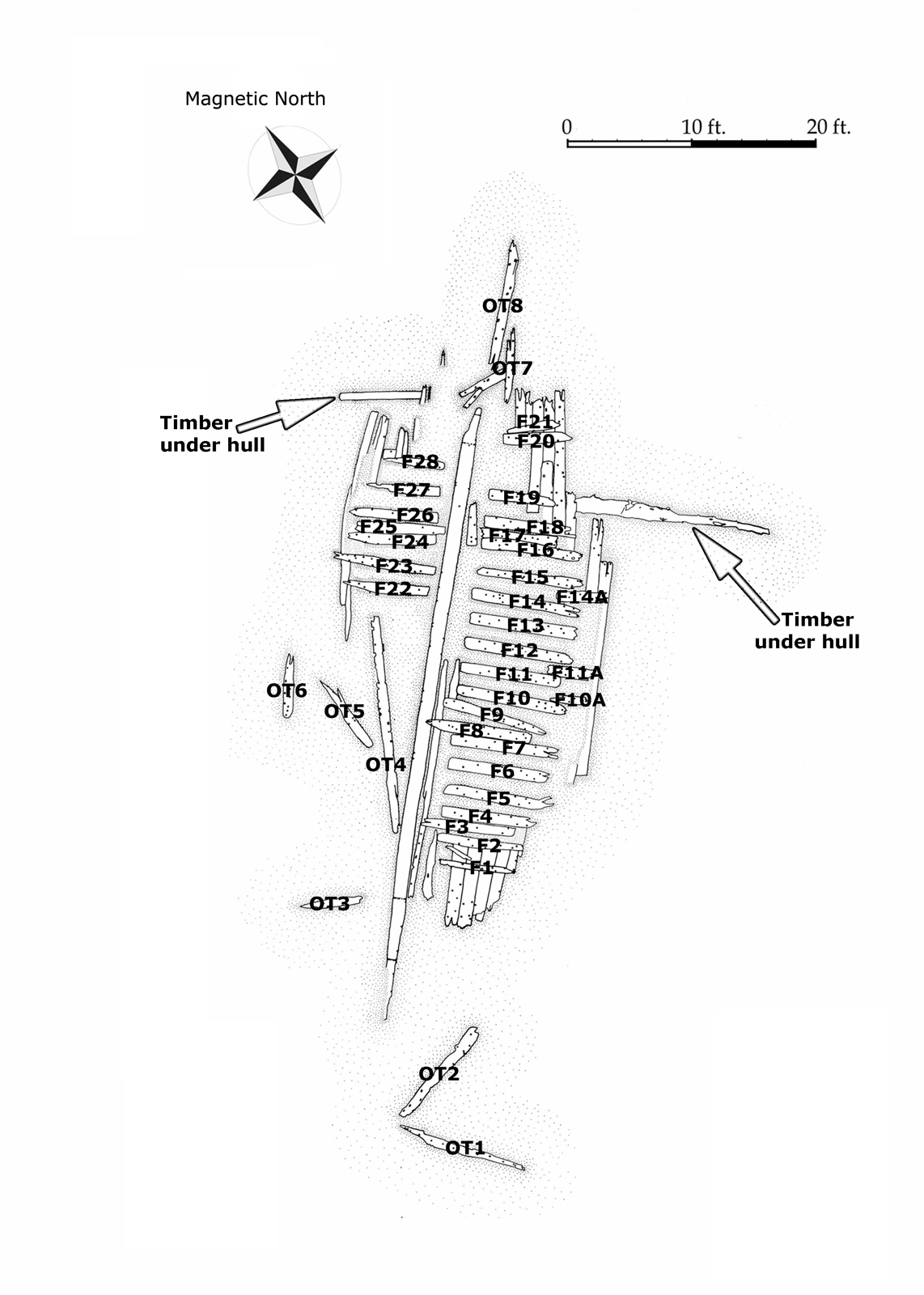

As units of measurement, data were recorded using feet and tenths of feet. For frame and treenail measurements, feet and inches were used. The site was mapped in plan view at a scale of 1 in. = 2 ft., using a combination of baseline offsets and trilateration. All associated continuous structure, and potentially associated elements within 10 ft. of the vessel structure, were included. Timbers further away, and a few small pieces of wood between 4 ft. and 6 ft. to the west of frame F3, were not mapped. Time considerations dictated that boulders and rocks were left off the site plan. Investigators ran a polypro baseline between two boulders, making it taut with a come-along. The baseline, oriented at 30° from magnetic north, remained in place during the duration of the project.  To ease discussion of vessel parts, the frames were numbered F1 to F28 beginning on the eastern side heading northward, F1 to F21, and then following the same procedure for the remaining frames on the western side, F22 to F28 (Figure 6). Three partial frames at the turn of the bilge were given the numbers F10A, F11A, and F14A. Volunteers recorded maximum molded and sided dimensions of each of the frames. Potential parts disassociated from the continuous wreckage were designated as outliers and numbered OT1 to OT8. It is not known with certainty that these are parts of the vessel, but they were mapped into the site plan because they exhibit similar characteristics in terms of size, fasteners, and erosion. Investigators moved outlier OT4 from its location across the western frames to the mud beside the keel. Photographs from 2006 and 2007 show that it has been moved to different locations on the western side of the site in the past.

To ease discussion of vessel parts, the frames were numbered F1 to F28 beginning on the eastern side heading northward, F1 to F21, and then following the same procedure for the remaining frames on the western side, F22 to F28 (Figure 6). Three partial frames at the turn of the bilge were given the numbers F10A, F11A, and F14A. Volunteers recorded maximum molded and sided dimensions of each of the frames. Potential parts disassociated from the continuous wreckage were designated as outliers and numbered OT1 to OT8. It is not known with certainty that these are parts of the vessel, but they were mapped into the site plan because they exhibit similar characteristics in terms of size, fasteners, and erosion. Investigators moved outlier OT4 from its location across the western frames to the mud beside the keel. Photographs from 2006 and 2007 show that it has been moved to different locations on the western side of the site in the past.

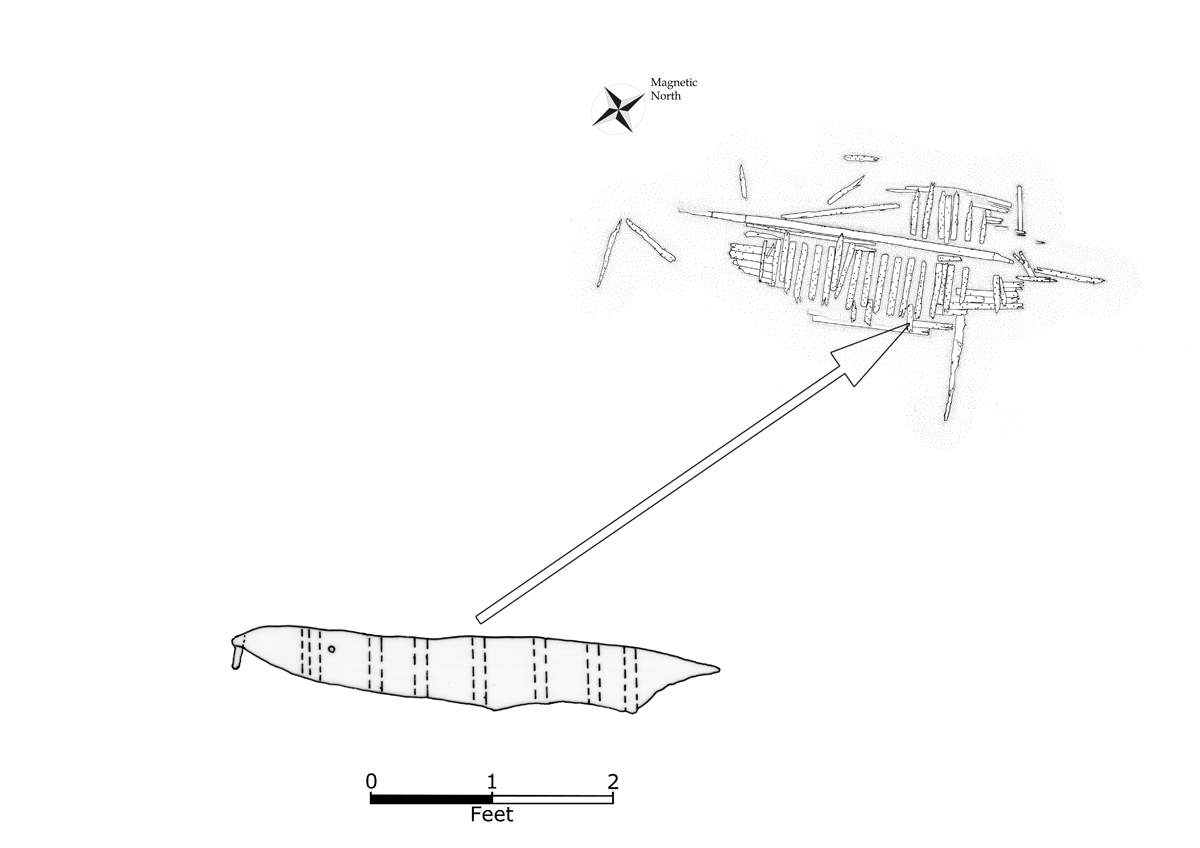

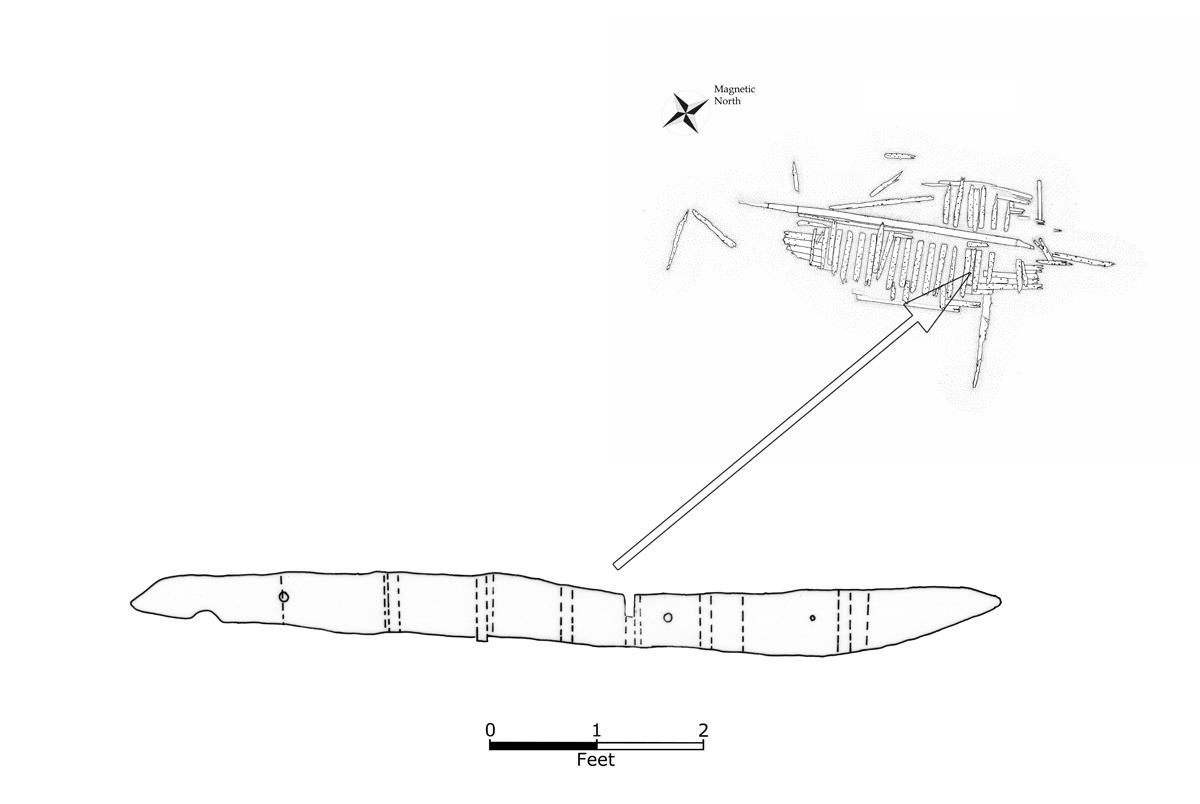

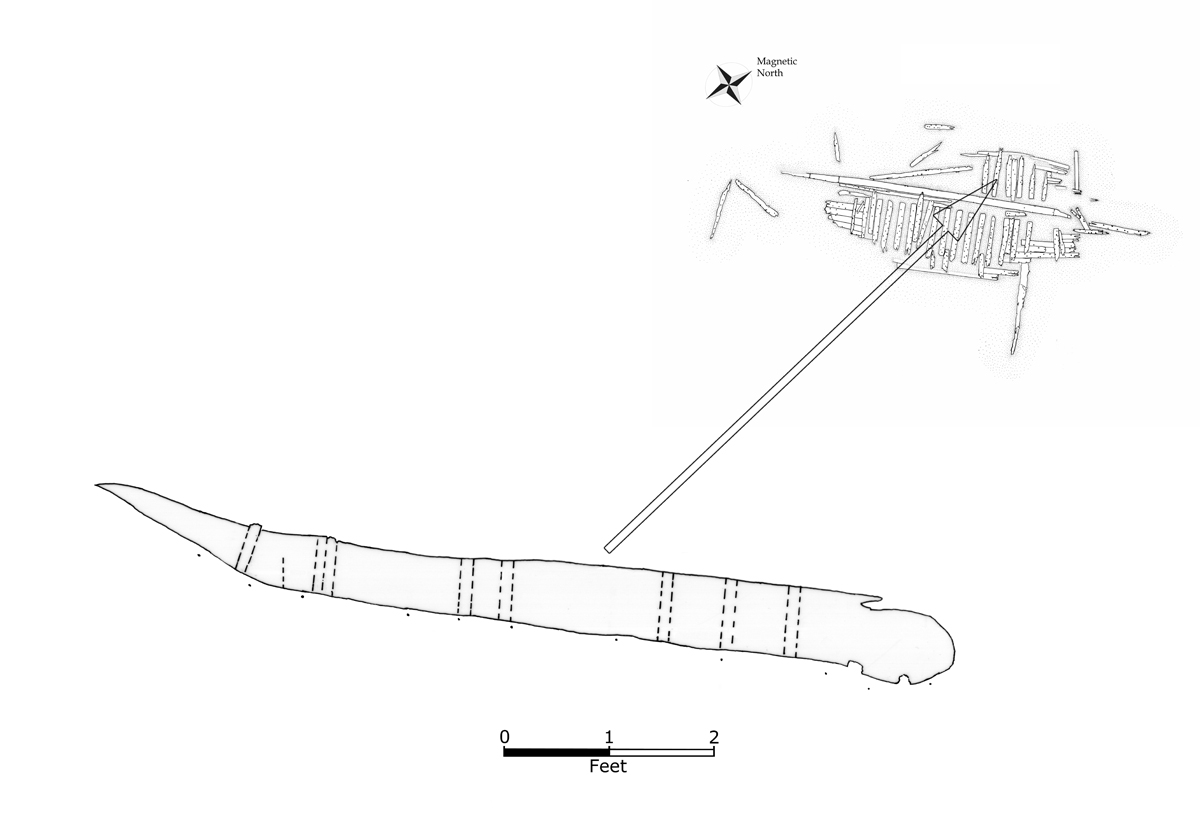

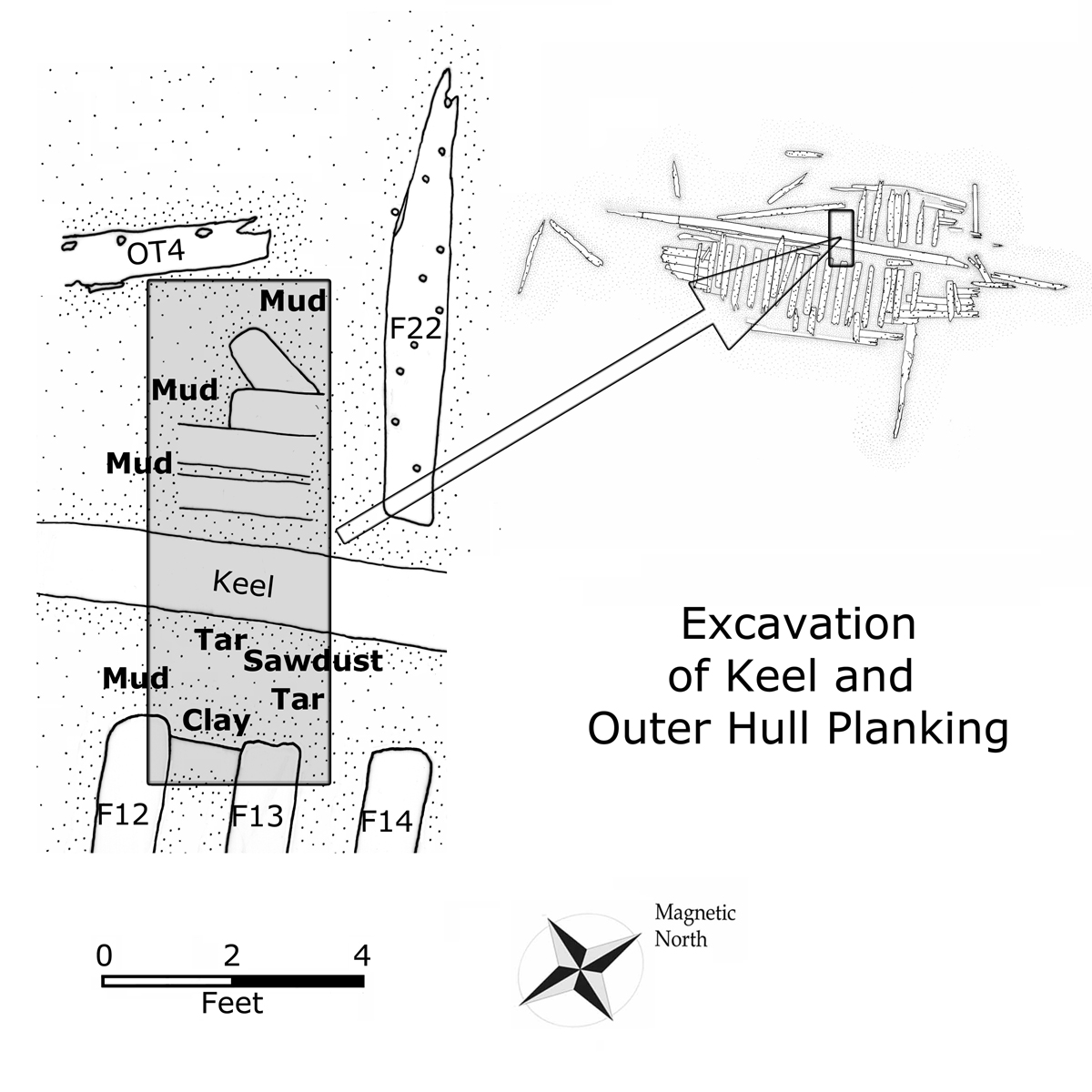

The research design called for a predominantly non-intrusive survey, with the option to excavate around the keel to gather information regarding its shape and dimensions. Investigators excavated the keel between 32 ft. and 34 ft. on the baseline in the vicinity of frames F12 and F13. Profiles were taken of frames F9, F14A, F16, and F23, noting fasteners on the last three (Figures 7-10).

The research design called for a predominantly non-intrusive survey, with the option to excavate around the keel to gather information regarding its shape and dimensions. Investigators excavated the keel between 32 ft. and 34 ft. on the baseline in the vicinity of frames F12 and F13. Profiles were taken of frames F9, F14A, F16, and F23, noting fasteners on the last three (Figures 7-10).

Measuring from string-leveled twine, these were drawn at 1 in. = 1 ft. to more easily capture details that might be lost at a smaller scale. A cross section of the keel was recorded at 32.7 ft. on the baseline within the excavated area.

OBSERVATIONS

The width of the remaining continuous structure is 22.65 ft., with a timber that the hull rests upon extending farther than that to the eastward. The overall dimensions of the site, including scattered nearby elements from the vessel, is 74 ft. roughly north south by 42 ft. roughly east-west. The three remaining structural features are the keel, the frames, and the outer hull planking.

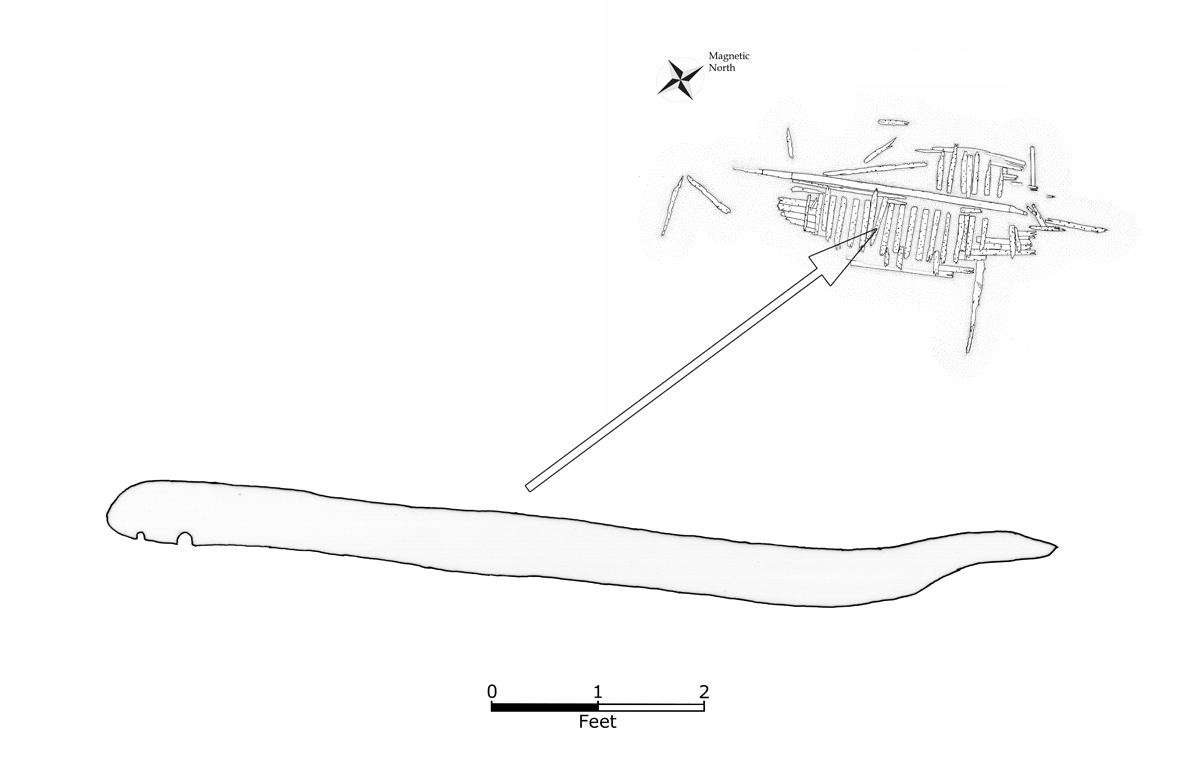

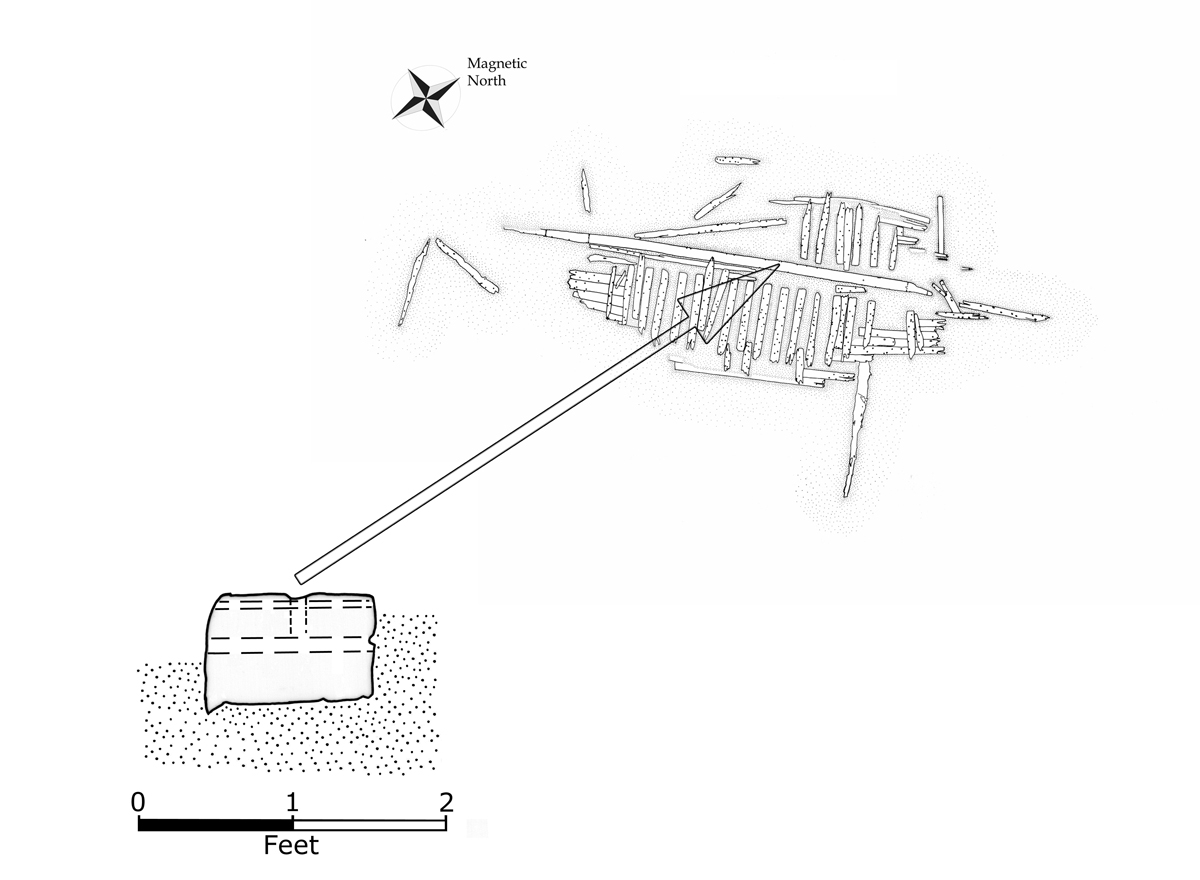

The keel is 49.85 ft. long, approximately 14 in. (1.17 ft.) sided and between 7¾ in. and 8¾ in. (0.63 ft. and 0.73 ft.) molded (Figure 11). The latter measurement was taken on a part of the structure that may have been damaged. The keel is uneven, the eastern edge retains a pointed piece that is absent on the other side. The original dimensions for the keel may have been 14 in. by 9 in. Whether intentional or formed by a split in the wood, the odd shape of the keel is curious, and at this point unexplained.

During the course of excavations near the keel investigators found sawdust, tar, coal, and mud above a substrate of clay. Upon learning that sawdust was discovered in the sediment by the keel one lobsterman/boat builder noted that a cheap way to caulk seams was to careen a vessel and put sawdust and mud into the seams, when the tide rose the water would push the mixture into the cavities (Wayne Rich Pers. Com.). Of course, the sawdust could also have been from cargo, as packing material, or from the historic sawmill nearby, but this use in repair provides one potential explanation for its presence. The keel excavations also revealed a section of the outer hull planking on the west side (Figure 12 and 13).

One rounded timber, likely not part of vessel structure, protrudes from underneath the outer hull planking. Two others found under the vessel, a large timber under the east side at F19, and another to the northwest in line with the end of the keel, suggest that the vessel may have been up on logs or timbers at its final deposition. A graphite rod, approximately 3⅛ in. long, was found and returned to this area (Figure 14). Volunteers partially excavated another portion on the east side of the keel between 19 ft. and 23.5 ft. on the baseline, near frames F5 and F6. Coal pieces were discovered at that location, as well as eroded timbers still present under the keel. The lip on the underside of the keel at this place was greater than 0.1 ft. (slightly over 1 in.).

The vessel exhibits a wide variation in frame dimensions. It is difficult to determine whether this is a function of their degraded nature or a variety of sizes on the original vessel. The smallest frame measures 6 in. by 6 in., significantly smaller than any of the other remaining frames. The largest sided width is 11¼ in. and the largest molded height is 7½ in. Frames are not square; the upper edges are rounded from erosion. The room and space pattern is approximately 2 ft., but some of the frames may have moved from their original positions.

The vessel exhibits a wide variation in frame dimensions. It is difficult to determine whether this is a function of their degraded nature or a variety of sizes on the original vessel. The smallest frame measures 6 in. by 6 in., significantly smaller than any of the other remaining frames. The largest sided width is 11¼ in. and the largest molded height is 7½ in. Frames are not square; the upper edges are rounded from erosion. The room and space pattern is approximately 2 ft., but some of the frames may have moved from their original positions.

The outer hull planks were fastened through the frames with cylindrical wooden bolts, called treenails. At least two of the frames (F16 and F17) were pinned together with treenails. The frames also had metal fastener holes, some with what appear to be the remains of metal pins in them. It is not certain if the pins are blind fasteners or continue through the frames, but the treenails appear to be through-fastenings holding the outer hull planking and frames together. Volunteers noted sawdust, coal, tar, and brick fragments where some of the frames met the planking. Frame F23 is one example; investigators noted tar toward the inboard third near the outer hull planks along its south face.

The outer hull planking is 2¼ in. thick, a measurement found to be consistent at several points. Chapelle discusses large American fishing schooners of the late nineteenth century as having outer hull planking 2½ in. thick, not far from the dimension recorded here (Chapelle 1994:568). A partial example of potential furring or sacrificial planking, a small piece of worm-eaten wood, is under the hull to the southeast end of the site. It appears fastened to the outer hull planking, but this has not been established with certainty. The planks meet at butt scarphs, and are attached to the frames in a treenail double fastener pattern (Desmond 1919:6).

As this was not an intrusive survey, on most of the frames the only fasteners recorded were those readily apparent, others obscured by sediment were certainly missed by investigators. The wreck exhibited three different material types of fasteners: wood, iron, and copper alloy. Of the extant fasteners, only wooden treenails were definitively identified, although circular holes with evidence of rust were observed, as well as ½ in. square holes that match a copper alloy fastener found on the northwest part of the wreck.

The treenails were of two sizes, 1¼ in. or 1½ in. in diameter, although the latter measurement may be the result of swelling of the wood outside of the fastener hole. Treenails were employed in three uses. First, they act as through-fastenings, running completely through both the outer hull planking and the frames. Second, they hold some frames together, as with the example of F16 and F17. Third, treenails were observed on the keel, driven vertically and horizontally, at least two examples of each (Figure 15). This is not particularly surprising, as it was not uncommon for treenails to be used in the keel (Chapelle 1969:178). All three treenails in the keel have 1¼ in. diameters. The treenails could be defined as un-wedged since neither wedges nor pegs were observed locking the treenails in place, but the ends of most of the treenails were obscured by sediment (McCarthy 2005:68).

The treenails were of two sizes, 1¼ in. or 1½ in. in diameter, although the latter measurement may be the result of swelling of the wood outside of the fastener hole. Treenails were employed in three uses. First, they act as through-fastenings, running completely through both the outer hull planking and the frames. Second, they hold some frames together, as with the example of F16 and F17. Third, treenails were observed on the keel, driven vertically and horizontally, at least two examples of each (Figure 15). This is not particularly surprising, as it was not uncommon for treenails to be used in the keel (Chapelle 1969:178). All three treenails in the keel have 1¼ in. diameters. The treenails could be defined as un-wedged since neither wedges nor pegs were observed locking the treenails in place, but the ends of most of the treenails were obscured by sediment (McCarthy 2005:68).

Treenails are especially suited to hold outer hull planking to frames because, unlike iron fastenings, they do not rust (Mccarthy 2005:64; citing Oliveira 1580:151). They are also noted for not “working slack” as iron fastenings can be prone to do (Holms 1908:260). Although employed in other tasks, fastening outer hull planking to the frames is their primary use in wooden shipbuilding. Some define them by this use entirely, designated the term to only those wooden pegs that hold outer hull planking to frames (Mccarthy 2005:64-65). Of the three varieties of treenails defined by De Kerchove, those on the Seal Cove Shipwreck appear to be “straight” treenails, cylindrical in shape (DeKerchove 1961:860).

As mentioned above, investigators noted no complete ferrous fasteners, although rust was observed in some of the otherwise empty fastener holes. As a mostly non-intrusive investigation, there was no probing of the fastener holes to ascertain the nature of remaining fragments. The keel revealed a variety of fastener sizes. Diameters of empty fastener holes along the keel were often difficult to conclusively ascertain, but varied from 1¼ in., likely treenail holes, to 1⅛ in., 1 in., and ¾ in. with this final measurement being confined to the western side of the keel. Deep sediment prohibited the investigation of much of the eastern face, and of most of the western face. A few of the observed fastener holes were located less than 0.12 ft. (1¼ in.) from the top of the keel, while others were as much as 0.37 ft. from the top. This curious pattern might suggest that the keel is currently on its side, with the top now facing west. More research needs to be done on site to determine if this is the case.

As mentioned above, investigators noted no complete ferrous fasteners, although rust was observed in some of the otherwise empty fastener holes. As a mostly non-intrusive investigation, there was no probing of the fastener holes to ascertain the nature of remaining fragments. The keel revealed a variety of fastener sizes. Diameters of empty fastener holes along the keel were often difficult to conclusively ascertain, but varied from 1¼ in., likely treenail holes, to 1⅛ in., 1 in., and ¾ in. with this final measurement being confined to the western side of the keel. Deep sediment prohibited the investigation of much of the eastern face, and of most of the western face. A few of the observed fastener holes were located less than 0.12 ft. (1¼ in.) from the top of the keel, while others were as much as 0.37 ft. from the top. This curious pattern might suggest that the keel is currently on its side, with the top now facing west. More research needs to be done on site to determine if this is the case.

A local informant provided investigators with a copper alloy fastener that he found on the site. It is square, ½ in. on a side (Figure 16). The dimension matches some of the fastener holes in outer hull planking, notably a well-preserved example on the western side of the wreck just north of frame F28. The fastener has been bent into a contorted shape, whether from stresses incurred as the vessel broke apart or if it were pulled from the wreck is unknown. Degradation of the metal is considerably more pronounced towards the head, where it may have been exposed to the elements. With the consent of the Town of Tremont, it is currently in the care of the Tremont Historical Society.

The vessel exhibits potential worm damage at three locations (Figure 17). One is on what could perhaps be sacrificial planking. If this is from teredo navalis, it may indicate that the vessel journeyed to outside the area because this wood boring marine mollusk is not native to the waters surrounding Mount Desert Island. However, it can be found as far north as Labrador and the Baltic (Grave 1928:260; Didžiulis 2011). It has been expanding its habitat up the Maine coast, observed as far northward as Stonington in 2001 (Darling Marine Center 2001:1). The damage needs to be further investigated before any conclusions may be drawn.

The vessel exhibits potential worm damage at three locations (Figure 17). One is on what could perhaps be sacrificial planking. If this is from teredo navalis, it may indicate that the vessel journeyed to outside the area because this wood boring marine mollusk is not native to the waters surrounding Mount Desert Island. However, it can be found as far north as Labrador and the Baltic (Grave 1928:260; Didžiulis 2011). It has been expanding its habitat up the Maine coast, observed as far northward as Stonington in 2001 (Darling Marine Center 2001:1). The damage needs to be further investigated before any conclusions may be drawn.

A lack of material culture associated with the wreck heightens the challenge of assigning a date range to this vessel. With only treenails, and perhaps one copper alloy fastener, to work with, it is likewise difficult to deduce when this vessel was built using fastener typology as a dating tool. It would be fair to estimate is that it is likely from anywhere between the early nineteenth to early twentieth centuries.

IDENTIFICATION

The site has proven difficult to identify, but local informants have provided some clues. Stanley Black of Tremont was told by his father that the wreck was an abandoned stone barge (Stanley Black, Pers. Comm.; Price 2007). There is a valid argument that the site represents an abandoned vessel. Its deposition out of the shipping channel and near a center of industry is consistent with abandoned watercraft patterns in other parts of the United States and abroad (Shomette and Eshelman 1982:583; Richards 2002:231; Price 2006:127). This site has all three of Richards’ features of abandonment: it lacks propulsion artifacts, has “a scarcity of portable material culture,” and has “highly articulated structural remains” (Richards 2008:145). Its location could be interpreted as further evidence against it being a true shipwreck. Its placement makes it an unlikely place to have been blown ashore.

The site has proven difficult to identify, but local informants have provided some clues. Stanley Black of Tremont was told by his father that the wreck was an abandoned stone barge (Stanley Black, Pers. Comm.; Price 2007). There is a valid argument that the site represents an abandoned vessel. Its deposition out of the shipping channel and near a center of industry is consistent with abandoned watercraft patterns in other parts of the United States and abroad (Shomette and Eshelman 1982:583; Richards 2002:231; Price 2006:127). This site has all three of Richards’ features of abandonment: it lacks propulsion artifacts, has “a scarcity of portable material culture,” and has “highly articulated structural remains” (Richards 2008:145). Its location could be interpreted as further evidence against it being a true shipwreck. Its placement makes it an unlikely place to have been blown ashore.

Local informants provide more information regarding the site. An informant recounted that in the 1970s he paced the vessel’s length at approximately 85 feet, considerably more structure than remains today (Maine Historic Preservation Commission 2007:1-2). A third man recalled playing on the wreck when he was a child (Carl Butler Pers. Com.). This gives an idea for how long the wreck has been there; he is now seventy years old and recalls that it was an old wreck even then. Aerial photographs of Seal Cove from 1964 show the wreck visible from the air.

Rinaldo

Rinaldo

If the Seal Cove wreck represents a catastrophic loss, two potential candidates emerge from historic records. The first is Rinaldo, lost in 1876. It was a 20.69 ton schooner that hailed from Southwest Harbor, although in 1869 it had Deer Isle listed as its homeport (United States Treasury Department 1869:204). It was run aground after breaking loose from where the “vessels had been lying during the winter,” presumably the current anchoring area in Seal Cove (United States Life-Saving Service 1876:28; United States Treasury Department 1877:148). The size of the vessel is quite small for the wreckage in Seal Cove.

Levant

A second candidate is the schooner Levant, forced ashore on the northern side of Seal Cove in December of 1884. A description of the conditions of the incident simply reads “heavy wind rough sea dark” (United States Life-Saving Service 1884:15). Like Rinaldo, at the time of loss it was registered out of Southwest Harbor. According to records in 1883, its hailing port was Bangor and it was built in Stockton, Maine, in 1846. Levant has a gross tonnage of 59.98, was 68.4 ft. long, 20.4 in beam, and had a 6 ft. depth of hold (American Shipmasters’ Association 1883:34). Constructed with iron fasteners, it was rebuilt in 1866 and by 1883 was registered as having iron and copper fasteners (New York Register 1857:251; 1858:276; American Shipmasters’ Association 1883:34). Although copper fastening is consistent with the copper alloy fastener potentially associated with the site, Levant may be too narrow in beam to be the Seal Cove wreck.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

The wreck at Seal Cove is a valuable archaeological resource that provides an opportunity to learn more about the construction of historic wooden vessels. Further data collection is recommended, including detailed drawings of the frames in plan view, profile, and cross section. A thorough recording of outer hull planking could reveal more about how it was constructed, as would a more detailed look at fastener patterns. Investigators could generate profiles across the site to better understand the relationship between its physical deposition and the site formation process.

More research needs to be done if this vessel is to be identified. Other researchers have had success in vessel identification using the American Shipmasters Association Rules for vessel construction (Russell 2002). Similar research using official records and shipbuilding treatises is recommended for this site. At the very least such a study could provide an estimation of the size range of the vessel. It may prove impossible to definitively identify the wreck at Seal Cove, but various sources may give researchers an idea of its original dimensions from the sizes of the remaining component parts.

Dendro-analysis could prove useful in determining the age and origin of the wood used in constructing the vessel. Learning the wood species of scantlings may provide only circumstantial evidence towards vessel identification, but it could rule out possible candidates. As an example, Levant was constructed of mixed hardwoods such as beech, birch, or elm (American Shipmasters’ Association 1883:34). If the wreck at Seal Cove was not constructed of these materials, that would rule out Levant as a candidate.

As this project illustrated, the Seal Cove shipwreck represents an excellent resource for teaching and outreach in the field of maritime and nautical archaeology. Its placement in the intertidal zone allows non-divers to participate in the process of shipwreck archaeology. It strongly suggested that any future fieldwork on the wreck would continue to involve the public.

CONCLUSION

Not including the author, no less than twenty people were involved in fieldwork at the Seal Cove wreck, making the outreach objective of the project a success. Despite limitations the investigators gathered significant data on a previously un-studied vessel, produced a site plan, and shed some light on the mystery of an historic wooden shipwreck on the western side of Mount Desert Island, Maine. In the process Acadia National Park staff and members of the public were given an opportunity to participate in a project that not only exposed them to maritime archaeology in practice, but gathered substantive data.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author wishes to thank East Carolina University Graduate Student intern Charles Bowdoin, Rebecca Cole-Will and David Manski of Acadia National Park, and volunteers Clare Anderson, Leighanne Bird, Muriel Davisson, Bruce Denny-Bryan, Jack Hirschenhofer, Robyn King, Shari Latulippe, Nanette Melero, Tony Menzietti, Kate Pontbriand, Sarah and Larkin Post, Ailin Rafferty, Laura Stevens, Chris Wiebusch, and Karen Zimmerman. Thanks to Tony Booth for his 2007 Total Station data and his help in negotiating the Maine Historic Archaeological Sites Inventory, and thanks to Stanley Black, Carl Butler, George Carter, Frank Reed, and Wayne Rich for their information about the site. Thanks to Joshua Daniel of Tidewater Atlantic Research, Steve Dilk of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, and Matthew DeFelice of the Broward County Historical Commission for their assistance in editing this document. Special thanks to Zach Whalen for his volunteer hours and for sharing his research from the National Archives, and to the National Park Service Submerged Resources Center and the Institute of Maritime History for providing the funding that made the project possible.

REFERENCES CITED

American Shipmaster’s Association

1883 Record of American and Foreign Shipping. American Shipmaster’s Association, New York, NY.

Chapelle, Howard I.

1969, Boatbuilding: A Complete Handbook of Wooden Boat Construction. W.W. Norton and Company, New York, NY.

1994, The American Fishing Schooners: 1825-1935. Reprint of 1973 Edition. W.W. Norton and Company, New York, NY.

Darling Marine Center

2001, Shipworms bore the Maine Coast. Making Waves (5) 2001.

De Kerchove, René

1961, International Maritime Dictionary. Second Edition. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York, NY.

Desmond, Charles

1919, Wooden Shipbuilding. The Rudder Publishing Company, New York, NY.

Didžiulis, Viktora

2011, NOBANIS, Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet- Teredo navalis. Online database of the European Network on Invasive Alien Species. www.nobanis.org, date of access 10/28/2011.

Dodge, Ezra A.

1871, Mount Desert Island and the Cranberry Isles. N.K. Sawyer, Ellsworth, ME.

Grave, W.H.

1928, Natural History of Shipworm, Teredo navalis, at Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Biological Bulletin (55): 260-282.

Holms, A. Campbell

1908, Practical Shipbuilding: Volume 1. Longman’s, Green and Company, New York, NY.

Lapham, W.B.

1886, Bar Harbor and Mount Desert Island. Press of Liberty Printing Company, New York, NY.

Maine Historic Preservation Commission

2007, Maine Historic Archaeological Sites Inventory: Site Number ME 436-028. On File at the Maine Historic Preservation Commission, Augusta, ME.

McCarthy, Michael

2005, Ships’ Fastenings: From Sewn boat to Steamship. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

New York Marine Register

1857, New York Marine Register. R.C. Root, Anthony & Co., New York, NY.

1858, New York Marine Register. R.C. Root, Anthony & Co., New York, NY.

Oliveira, F.C.

1580, Livro da fabrica das naos. 1991 edition. Academia de Marinha, Lisbon, Portugal.

Peters, John

1795, A Plan of Mount Desert. Map on File at the William O. Sawtelle Curatorial Center, Acadia National Park. Bar Harbor, ME.

Price, Franklin H.

2006, Conflict and Commerce: Maritime Archaeological Site Distribution as Cultural Change on the Roanoke River, North Carolina. MA thesis, Department of History, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

2007, Blue Hill and Frenchman Bays Fishermen Interview Project. Report on File at the Maine Historic Preservation Commission, Augusta, ME.

Richards, Nathan

2002, Deep Structures: An Examination of Deliberate Watercraft Abandonment in Australia. PhD dissertation, Department of Archaeology, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia.

2008, Ships’ Graveyards: Abandoned Watercraft and the Archaeological Site Formation Process. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

Russell, Matthew A.

2002, Beached Shipwrecks from Channel Islands National Park, California. Journal of Field Archaeology 29(3/4): 369-384.

Street, George E.

1905, Mount Desert: A History. Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, Boston, MA.

United States Life-Saving Service

1876, Report No. 14. United States Life-Saving Service. National Archives. Boston, MA.

1884, Record of Wreck Reports. Report No. 5. United States Life-Saving Service. National Archives. Boston, MA.

United States Treasury Department

1869, Merchant Vessels of the United States: Second Annual Report. United States Treasury Department, Washington, DC.

1877, Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service. National Archives. Washington, DC.