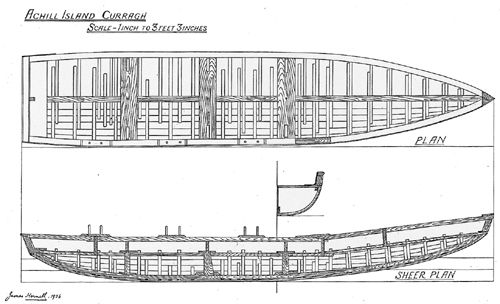

As in other colonial settings, indigenous and vernacular watercraft, notably the skin-clad curragh and wooden-planked yawl, played a central role in long-standing maritime lifeways and practices on Achill. Curraghs are the famed skin or canvas boats used for centuries along the western seaboard of Ireland. Curragh designs vary from island to island and coast to coast. In 1936 an Achill curragh from the village of Keel was recorded by the British maritime historian James Hornell.

He presumably chose a representative vessel typical of Achill construction. Since that time, the Achill curragh has undergone a series of changes, many of which were instigated by the brief flourishing of the basking shark fishery in the mid-20th century, and the increasing availability of outboard motors. These design changes included lowering the stern so that a struggling shark could not easily tip the boat, and changing the thole pins (which hold the oars in place) so that they served as a quick release for the oars, for that same reason. The curraghs today tend to be shorter and feature a square transom which will more easily accept an outboard motor. Also, today’s curraghs are much heavier and are sometimes fiberglassed.

The curraghs recorded by Hornell in 1936, and those in use today, feature wooden planking on their interior, with tarred canvas stretched over their exterior surface to make the boats waterproof. Earlier Achill curraghs did not have planking on their interior, which appears to be an innovation introduced to the island with lobster fishing. The earlier curraghs featured canvas (and even earlier still, skins) over a light wooden framework, without an interior floor of planking. This made for a much lighter and more maneuverable craft, at the expense of stability. These curraghs can be seen in this 1890s photograph of a curragh landing place at Dooagh Beach.

This photograph shows how these watercraft were an everyday part of village life, playing an integral role in the in the formation of community identity, and how visible they were on the maritime landscape. Below is a detail of this photograph, where it can be seen that these late 19th century curraghs did not have planking.

We have tried to identify as best we can the exact location that this scene took place over 100 years ago. It appears to be a spot on the beach a little to the east of the current Dooagh pier, which may be about the same age. Near this location is a gap in the rocks that almost appears to be a natural boat ramp, carved out of the landscape by glacial action. Local memory indicates that this formation was a curragh landing place, known as “Leck.” We do not yet know the meaning of this term, which might have some special significance in Gaelic. But it appears likely that the gathering of curraghs in the above photographs was near this natural formation.

Just west of this is the current pier at Dooagh, which locals tell us is probably 80 to 100 years old. We have been hoping to go diving, but the seas have been very heavy for several days—this is obvious from this picture, which shows the waves crashing over the breakwater at Dooagh pier.

Since we cannot dive, we have decided to spend some time recording the curragh pens, another of our research objectives. These “pens,” located adjacent to the pier, are storage places or berths for the curraghs, which are still used on the island. As these boats were traditionally lightweight, and this island is known for its strong winds, a secure boat storage area was vital for the islanders who depended on them for subsistence fishing. Today, throughout most of Ireland, curraghs are stored on racks. The pens on Achill are the only known such pens remaining in Ireland.

The Dooagh curraghmen appear to have taken advantage of the natural topography to carve out hollow spaces that would shelter their boats from the wind. Spoil from this activity was deposited on either side of the hollows, forming a greater wind-block, and the spaces were shored up with low stone walls, which defined the perimeter of individual pens and also helped shield them from the wind. Sometimes instead of consolidated stone walls there are simply as series of stones in a line on either side of the pen. The more modern version involves casting or using store-bought cement blocks with tie-off rings, upon which the curraghs sit and can be secured to with line.

After a quick survey of this curragh pen area we have identified at least 20 individual pens. Most of these have been abandoned, as only five curraghs are currently being stored here. Locals we have talked to indicate that these pens have been in for perhaps 100 years, which would make them likely to be contemporaneous with the historic photographs of curraghs at Dooagh beach.

In order to produce a map of the curragh pen area, we lay a baseline out along its entire length. From two datums on the baseline, we use tape measures to triangulate the positions of individual features on each pen, so that we can reproduce a plan view on paper back at our headquarters. We are starting on Pens 8 and 9, where Chuck stretches the tapes and calls off the readings to Kevin, who is recording these measurements on a sketch.

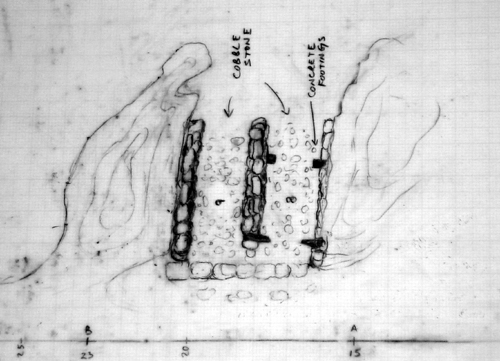

Back in the lab, Kevin produces a scaled plan drawing of Pens 8 and 9.

The preliminary drawing of these two pens, which incorporate natural hollows of the topography buttressed by spoil piles and shored up with low stone walls. The floors of the pens feature cobbles which would have kept the curraghs up off the wet ground. The pen on the right, Pen 8, has been modified by the placement of poured cement footings, which would support the curragh completely off the ground and provide iron rings to tie it down with.

The following day we are stuck inside during a gale, but the day after we return to the pier to draw a profile of Pens 8-9.

Chuck takes measurements down to various points on the structure from a leveled line suspended over the pens.

Then Kevin uses these measurements to produce a scaled drawing of the structure’s cross-section.

Adjacent to the pen area is another enclosed field with two abandoned curraghs. They appear to have been left as derelicts in their pens to rot away. A local informant tells us that one of them was a skea, a more round-hulled curragh than those built today, and that after its owner’s death it was burned and left to deteriorate by his family members. Michael Gielty, the long-time proprietor of Gielty’s Pub, has told us that curraghmen would make their own pens, which would be used solely by them, until they sold their boat or otherwise stopped using their individual pen. An unused pen could then be used by another islander to store his own curragh. In this case the curragh was left in place and has never been removed, a testament to the life and livelihood of its original owner.