Our final team member has arrived. Dr. Sam Turner is the Director of Archaeology for LAMP (Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program) and also the President of IMH (Institute for Maritime History), two of the institutions sponsoring this research project. He flew in from Florida last night to work with us for our final two weeks on Achill.

On Monday we cannot dive because our boat was already chartered for a group of sport fishermen, which is just as well because Sam will be dealing with jetlag and everyone should be in top condition for these dives, which will be relatively deep (90 feet or 26 m). Instead we stay the night at our friends the Shanleys in Westport, and allow Sam to sleep in Monday morning. In the afternoon, the crew decides to climb Croagh Patrick, the holy mountain which has been a pilgrimage site for thousands of years. Here is Sam near the top of the mountain.

The evening view of a mist-shrouded Clare island from the top of Croagh Patrick. Our first dive the following morning will take place just off this island, which is directly south of Achill.

The next morning dawns and we are in Achill. We are meeting our boat at Kildavnet pier, right next to the tower house built by the powerful O’Malley clan, whose most famous member was the 16th century Pirate Queen Grace O’Malley. Here Sam chats with our captain, local boatbuilder John O’Malley, a descendant of the original owners of the tower.

The Clare Island Fish Farm, whose facilities are located on the former site of a 19th century Coastguard station on Achill at Cloghmore, has agreed to let us use their banks to fill our scuba tanks. Their underwater salmon pens are close to the first shipwreck we will be diving on each day. Every morning we arrive early, drop off our gear at the pier, drive down the road to the Fish Farm to fill the tanks, and then return to the pier to meet the boat for our dives. Then we set off for our first dive on the shipwreck we have nicknamed the “Train Wreck.” Here LAMP archaeologists Chuck Meide and Sam Turner prepare for the first dive on this wreck shortly after anchoring off Clare Island.

The wreck is located in an anchorage under the Clare Island Lighthouse.

This light station was established in 1806 to mark the safe route between Clare Island and Achill Island. Entering Clew Bay below Clare Island was a much more dangerous route, fraught with barely submerged rocks. The area to the southwest of the lighthouse was a safe anchorage with sheltered from the prevailing winds by the bulk of the island.

The shipwreck below, unlike the Jenny at Achill Beg to the north, is intact and appears to have foundered while at anchor. It is believed that the ship was plying a coastal route and sprung a leak. It probably made it to this anchorage, where repairs were attempted, but due to the heavy cargo the bottommost part of the ship was inaccessible and, probably after hours at the pumps, she sank to the bottom in 90 feet of water. Local divers discovered the site and noticed that the ship was loaded with a cargo of what appeared to be train parts. Railroads came to this area in the 1880s, and the ship might date to this period.

Anchored over the site, we are excited about seeing this shipwreck for the first time. Norine Carroll and Captain O’Malley help Sam gear up for the first dive.

At a depth of 90 feet, the divers will only have 30 minutes of working time to descent to the wreck and accomplish their goals. Staying any longer will put them at risk of developing decompression sickness or the bends, which is caused by a build-up of nitrogen in the divers’ bodies. We are using U.S. Navy diving tables, which help us plan safe dive times depending on what depth we will be working at. Once geared up, Sam enters the water.

The divers submerge and descend down stout line which is anchored on the bottom somewhere near the wreck. Sam’s buddy for this dive is Kevin Cullen, graduate student from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Their task for this first dive is to locate the wreck, which they will do by swimming a circle search. This is done by hammering a stake of iron rebar into the bottom, stretching a tape measure out from it and swimming in a circular search pattern, hoping to either see or snag the wreck. Here Sam has set up the search line, and is taking a compass bearing so that he will know when they have completed a full circle.

But the divers are lucky, and they come upon the wreckage almost immediately! Spread out before Sam and Kevin is a large pile of debris, including a wide variety of iron objects covered with a layer of concretion and sea growth.

Most of these objects are not easily recognizable, but the divers do think much of this sunken cargo might be train undercarriage components.

Sam and Kevin slowly explore the large, oval-shaped mound of wreckage, which is over ten meters in length.

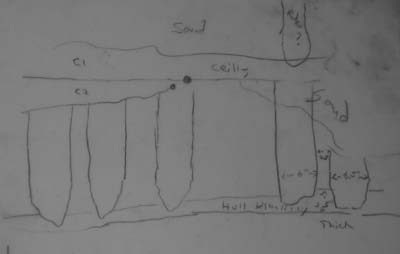

At the far end of the wreck, believed to be the stern end, Sam notices wooden hull timbers protruding from the sand.

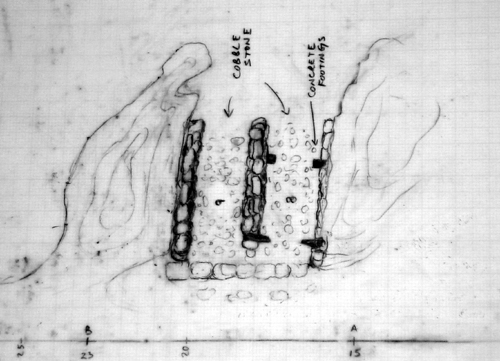

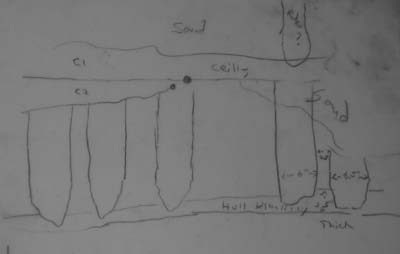

This certainly confirms that this ship was a wooden-hulled vessel, and closer inspection of the hull remains will help us better understand its construction and possibly let us date the vessel. There is still enough time for Sam to start a scaled drawing of the hull remains, which he will end up finishing on his dive tomorrow.

Sam’s drawing of the hull remains as sketched after his first dive.

After the completion of the first dive, Chuck Meide and Norine Carroll enter the water. Our task is to first move the heavily weighted buoy line to the wreck and tie it off to the wreckage, and then if time allows to set in a baseline over the wreck in order to accurately map its dimensions and layout on future dives. Dragging the buoy line underwater is a more difficult task than initially envisioned, as its weights are heavy and pulling over 90 feet of line and two buoys through the water column is a significant task. But the task is completed and the line is tied off to the wreck, so that we will have a direct line from the surface to the shipwreck for descents and ascents.

During our dive we notice an abundance of marine life, including several conger eels like the one pictured here. These cold-water cousins of the moray eel can deliver a dangerous bite if provoked.

Our final task is to lay in a baseline. After struggling to deal with the buoy, we have burned a lot of air and are limited on time, but we manage to use a hammer to pound in two rebar stakes, one at each end of the wreck. Between these we string a tape measure directly across the center of the shipwreck’s cargo pile. From this baseline we will be able to measure offsets from known points on the line to the edges of the pile, or to individual objects, to produce a map of the shipwreck.

After every dive, we pause on our ascent line at a depth of around 15’ for a safety stop. This allows the divers to off-gas some of the nitrogen that has built up in their system during the dive. We have decided to conduct a 7 minute safety stop after every dive on this wreck, which would be the mandatory stop time if we were to stay on the bottom for longer than the prescribed 30 minutes. Here is Norine at the safety stop.

Back on the boat, we relax for a bit after the dives. Everyone is excited after this dive. This shipwreck is intriguing, very intact, and simply a great dive! We are also pleased that we have accomplished so much on the first day of diving on it. After two dives, we have located the wreck, established a buoy line to it, begun recording the wreck, and set a baseline in place for further mapping operations. We consider this a very successful start to the investigation of this mystery wreck. But now it is time to leave Clare Island for our second dive, on the 1894 wreck of the Jenny.

Located only about 4.1 km or 2.6 miles away from the Train wreck, the wreck of the Jenny is in a completely different environment, and that has drastically affected the site formation processes that have made this a scattered spread of wreckage over a rocky, high-energy, multi-depthed bottom as opposed to an intact deep-water wreck on a flat sandy bottom. It is challenging but fun to be working on two such different shipwrecks at the same time. Because of its depth, we could not do a second dive on the Train wreck, but as the Jenny is in only 35 feet of water it is well-suited for our second series of dives each day.

Our vessel the Naomh Davnait maneuvers in the waters over the Jenny, under the sight of the tall cliffs of Achill Beg and the Achill Beg Lighthouse to the east.

Here Sam and Kevin are deploying a buoy on some more of the scattered wreckage they have identified.

From that point they are swimming a search transect using a buoy to keep in a straight line at an angle of about 310 degrees. They stretch out a tape measure to act as a guideline, because it is very easy to get lost in all of these kelp-swathed gullies even with a compass.

They then search back and forth on either side of the tape measure line, marking any wreckage they find with flagging tape, such as these pieces of partially buried logwood.

One interesting artifact they come across is an intact hull timber with a large copper-alloy bolt. The bolt appears shiny and new because of the sand with is constantly moving back and forth across its surface with the surge, effectively polishing it. This would have been a large hull timber such as a section of the ship’s keel or a frame.

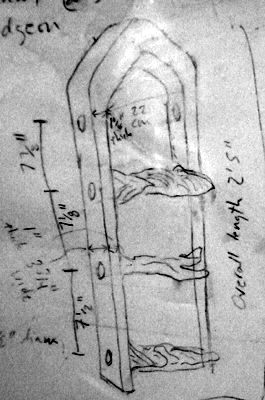

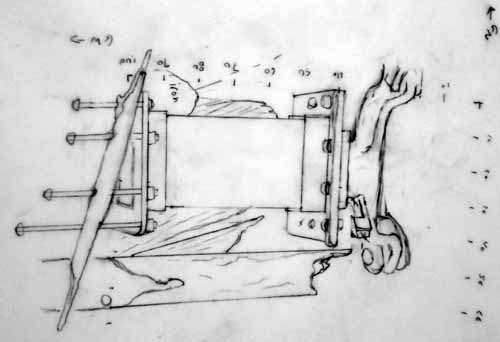

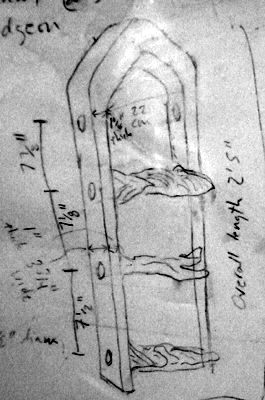

An even more exciting discovery awaits. Sam and Kevin have found a large brass fitting with wooden remains attached to its inner surface. Sam immediately recognizes it as one of the rudder’s pintles. This was a large, brass strap that wrapped around the rudder, featuring a sturdy pin on the inboard surface. This pin would have fit into the gudgeon, a similar strap that was attached to the stern of the ship, with a loop to accept the pintle pin. The rudder was hung onto the stern of the ship by these pintles, which allowed it to pivot and steer the ship. This find, located over 30 meters from the main cluster of wreckage which has been buoyed, marks the approximate location of the stern of the ship, though of course this vessel has broken up and lies scattered about. On a subsequent dive, Chuck measures the dimensions of and makes a detailed sketch of the pintle.

A buoy is tied off to the pintle so that it can be easily relocated, and so that we can see its position in relation to our other buoys once on the surface.

Chuck’s sketch of the pintle.

This is a photograph of the cove where we are diving, showing our boat at anchor near the site of the Jenny.

This detail of the above photo has been enlarged and labeled to show the boat in relation to the two buoys denoting the main cluster of artifacts, and the third buoy over the recently-discovered pintle.

Smiles are on everyone’s face after such great dives. The forecast is calling for good weather all week long, which is quite a rarity on Achill. With the acquisition of a good diving boat, the arrival of our full crew, and a week of good weather, things have really come together and we are expecting to accomplish a lot this week. As we motor back to the pier, we pass under the Achill Beg Lighthouse. It was built in 1965 to replace the light at Clare Island which went defunct when the light station passed into private hands. Our captain, John O’Malley, is not only a third generation boatbuilder but the keeper for this lighthouse. Sam and I also work at a lighthouse, back in St. Augustine, Florida with LAMP, so we are delighted to be diving on two shipwrecks under the reassuring gaze of two lighthouses.