15 August 2007: SHIP in Maryland and Delaware

We have almost finished work under the FY2007 grant from Maryland Historical Trust. We found several uncharted wrecks (some old, some new) and will finish mapping them during the next month or two. When those are done we will continue work wherever the Trust wants.

The project ran over time but under budget, with much more volunteer participation than we had planned or hoped. Thanks to all who joined in the effort!

During the first week of October we will recon the area around Lewes, Delaware, for the Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs, in cooperation and with the generous support of the Archaeological Society of Delaware. For a copy of the project plan, email david.howe@maritimehistory.org.

New Castle DE, final report

We filed our final report with the Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs. For a redacted copy of the report (without site coordinates) in Adobe, please email David.Howe@maritimehistory.org.

Achill Island Field Report 5: Hike to the Napoleonic Tower, 19 June 2006

We’ve had a few days of bad weather, and so haven’t gotten much work done. It has made for some interesting sights, though. Here the mist creeps over the crest of the mountain and threatens to engulf a holiday home below.

We’ve had a few days of bad weather, and so haven’t gotten much work done. It has made for some interesting sights, though. Here the mist creeps over the crest of the mountain and threatens to engulf a holiday home below.

The following day turns out to be nice, however. I have a friend visiting, John Bennett. He is an archaeologist who first came to Achill as a student in the Achill Archaeological Field School in 2003. John is a newly accepted graduate student at the University of Boston, and for the last two years he has participated in the ongoing archaeological excavations at Pompeii as an assistant field director. He has stopped by Achill for several days on his way to Italy for this summer’s Pompeii excavation, and has agreed to help with my research during his visit.

As I am interested in all aspects of the maritime landscape, not only those underwater or on the foreshore, I have always wanted to hike up to the ruins of a lookout/signal tower dating to the time of the Napoleonic Wars. It is situated on the top of a hill above the villages of Dooagh and Keel, some 194 meters above sea level, with a commanding view of both Clew and Blacksod Bays. These towers were a vital aspect of British imperial seapower in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. From its lofty perch, tower personnel could keep an eye out for enemy ships for miles out to sea, and relay messages from British ships on either side of the island, thus providing a reliable communication link between Clew and Blacksod Bays. This was done through a telegraph system using signal flags displayed in various positions to transmit coded messages.

In addition to providing a communication link for naval vessels, the tower dominated the local landscape and thus served as a prominent symbol of imperial authority overlooking the island. Residents of the Deserted Village, Dooagh, Keel, and other villages throughout the island would have seen this tower high above them on a daily basis. In this respect the structure served as a panopticon or all-seeing eye, reminding locals—who often chafed under British rule—that the authorities were always watching.

We start our hike near the Deserted Village, and make our way up Slievemore which, at 671 m is the tallest mountain on Achill. John wants to first visit a site he and another student discovered while hiking the mountain in 2003. This is a series of stone hut-like structures situated high on the mountain, overlooking Keel Bay. As they have never been excavated, their age and function remain a mystery. They could be prehistoric, they could be monastic spiritual retreats dating to the early Medieval period, they could have served as hiding places during Viking raids, they could be shepherds’ shelters dating to the later historic period, or they could be something else entirely. From a distance they are difficult to make out.

But closer up these semi-subterranean huts can be more easily discerned. The roof of the structure in the foreground has collapsed inwards, and two more huts are visible in the background. They were almost invisible when initially discovered, as they were covered with thick fern growth.

We continue the hike by turning west and heading towards the tower, which is visible on the next hilltop. As we march towards it, we pass over the Deserted Village below. The Achill Archaeological Field School has conducted excavations at a number of houses and other structures in the village since 1991. The Village, located at an elevation of between 50 and 80 m above sea level, consists of three concentrations of roofless stone houses connected by a relict roadway spanning a length of 1.5 km. It is the largest standing post-medieval deserted village in Ireland and possibly in all of Europe. Seventy-four houses remain standing of some 137 which were recorded on an 1837 British Ordnance Survey. It was occupied as early as the mid-18th century and abandoned sometime shortly after the Famine (1845-1850), its residents having moved to the village of Dooagh, probably to take advantage of its proximity to the sea. The Deserted Village continued to be occupied on a seasonal basis as a booleying village as late as the 1940s. Booleying was a practice where cattle were driven to upland locales during the growing season, to provide them with fresh mountain pasture for grazing and to allow lowland crops to mature undisturbed. Although we have learned much about the daily lives of the islanders who lived here through years of excavation, much of the history of this village, including its original name, remains a mystery.

Passing the village, we continue on the slope of Slievemore heading west. Before us, the tower (denoted by the black arrow) can be seen overlooking Blacksod Bay. It would have been visible not only from the Deserted Village but from much of Blacksod and Clew Bays.

Off in the distant expanse of Blacksod Bay looms another British sentinel: Black Rock Lighthouse.

The rugged nature of the surrounding maritime landscape is evident all around us. This is a view of the rocky shore fronting Blacksod Bay to the north. Off in the distance is the Belmullet Peninsula, which juts to the south and divides the Atlantic from the upper portion of Blacksod Bay. Sea caves like the ones visible in these pictures had long been used to smuggle goods into Achill to avoid paying customs dues, though the placement of the signal tower and Coastguard stations were designed in part to thwart this illicit activity.

Finally cresting the hill, the partially collapsed signal tower appears before us.

The tower is situated in a rectangular yard enclosed by the remains of a stone fence, delineating an area about 26 m by 50 m. The tower is roughly in the center of the enclosed area. This neat and orderly layout is typical of British military architecture, and can also be seen in the nineteenth-century Coastguard stations remaining on the island. Many archaeologists have suggested that this kind of imposing and symmetrical architecture was designed to impart a sense of orderliness and reinforce British authority and imperial ideology on the landscape. The low height of the wall, and lack of rubble indicating it was ever significantly higher, suggests that it may have served more of a symbolic rather than defensive role.

The tower is square, with exterior dimensions of 5.75 m by 5.75 m, and interior dimensions of 4.3 m by 4.3 m. Surrounding its remains are piles of rubble, suggesting it was once significantly taller. The north and south walls, facing the two bays, each featured two windows, though these have mostly collapsed. The east and west walls were solid.

John takes a break from measuring architectural features, and enjoys the view to the south over Clew Bay that British sentinels once shared.

A number of interesting architectural features are visible inside the structure. On the east wall was a central fireplace flanked by two inset niches which appear to have held storage shelves.

The image below shows the interior southern wall, where the remains of the two windows can be seen, along with a series of mortises (holes) in the wall below the windows which would have held wooden floor beams. These beams would have been planked to create a floor surface to walk upon, and the area beneath, at least 1.5 m in depth, would have served as storage space. A shaft in the eastern wall, to the right of the fireplace, provided ventilation to this area under the floor. Another ventilation shaft on the left side of the fireplace provided fresh air to the main chamber.

There is little evidence on the interior walls for an upper story. We would expect to find another series of floor beam mortises or put-log holes in the walls at the height of the upper floor, if there indeed was one. There is one large mortise in each wall (above and to the right of the fireplace), suggesting that there was at least one large beam crossing overhead, but it would not have been enough to support a floor, and its placement to one side, as opposed to the center, is also curious. There must have been a function for this beam, possibly to hold a ladder or suspend articles from, but it remains a mystery for now. It is also quite possible that the tower was significantly taller, and that as the upper portions of the walls are all missing the upper story floor mortises are no longer extant. The amount of rubble inside and around the tower indicate that this is a likely scenario. Fragments of roof slate found in the rubble outside suggest that its roof would have been slated, a common type of roof for this kind of architecture. Islanders’ cottages would have been thatched at this time, a cheaper but less durable form of roofing.

The picture below shows the east and south walls, depicting the fireplace (left), arched shelving niche, overhead beam mortise (left of shelving arch, and above and to the right of the fireplace), the sub-floor ventilation shaft (below shelving niche at corner), the floor beam mortises (bottom right, situated just above the ventilation inlet), and one of the two southern windows (missing its upper portion).

Looking out the southern windows, which command a view of Clew Bay, with the Minaun Cliffs on the left and Clare Island on the right. Another signal tower was built on Clare Island.

Outside the tower, in the western area of the enclosed yard, is a large depression measuring some 3 m across. Located about 12 m from the tower, it may have served as a latrine for the soldiers stationed here.

After we have recorded all of these features, we take a different route down the hill, through the old early twentieth century amethyst and quartz mining station. We make our way to the old road (ca. 1914) built for this operation. It runs right through the Deserted Village on its way to the sea, where minerals from the mine were shipped out from Purteen Harbour. These links between mountain and ocean remind us that on an island, even upland activities were part of an ongoing relationship with the sea.

Achill Island Field Report 4: Return to the Wreck of the Successful, 14 June 2006

Today’s plan is to visit the wreck of an old fishing trawler named the Successful. This vessel may have been originally built as early as the late nineteenth century, though it certainly operated through the first decades of the twentieth century. Around 1950 it was a derelict vessel in Westport, and it was bought by the Sweeny family of Achill Sound for only five pounds.

The Sweenys were involved in a variety of maritime enterprises including commercial fishing and shipwreck salvage, and the Successful was intended to support theses activities. While moored in the Sound, however, it ran aground during a storm and was abandoned after recovery efforts proved fruitless. Successful was both steam- and sail-powered, representing a short-lived hybrid vessel type during a period of rapid technological change in the British commercial fishing industry. The introduction of large steam-powered trawlers constituted the last stage of the transition from traditional subsistence fishing to commercial fishing that took place in the British and Irish isles over the nineteenth century.

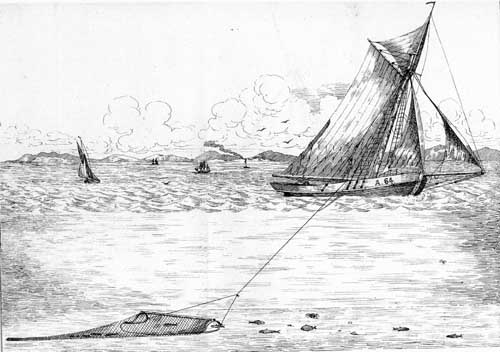

This picture above is from a book titled The Deep Sea and Coast Fisheries of Ireland, with Suggestions for the Working of a Fishing Company by Wallop Brabazon, published in 1848. It depicts a schooner-rigged sailing trawler of the type recommended by Brabazon for a profitable fishing endeavor in Irish waters. The boat is depicted underway hauling its trawl or nets. The Successful was a similar type of vessel, though it had two masts and an unknown rig. It also had a propeller driven by a steam engine. While the engine is missing (likely salvaged either before the vessel was sold to the Sweenys, or after its loss in the Sound) a boiler does remain on the wreck. It is very small for a ship this size, suggesting that Successful may have been underpowered, and might have used its small engine mainly to assist in maneuvering and to supplement sail power while underway. The ship may have been originally built as a sailing vessel, and had the engine added during a refit, in order to gain some more profitable years from an otherwise obsolete vessel. When investigating this wreck we are thinking about these kinds of research questions, and Successful promises to lend insight into how technological innovations were adapted in this localized maritime setting.

The wreck is located on the foreshore, the area of the sea-bottom exposed during low tide. It is situated in the Sound, north of the bridge and the town of Achill Sound (visible in the background of this picture). This makes it readily accessible to project archaeologists. Joining me today is Leonie Roy Archambault, an archaeologist who was a student in the 2004 Achill Archaeological Field School. She has returned to Achill to assist in the Field School, and has agreed to help me today on the shipwreck site.

The wreckage is covered with a thick growth of kelp and other seaweed. Our first step is to remove this growth by picking it off by hand, in order to visibly inspect the site. We spent some time recording the wreck remains last year, and the kelp has grown back since then.

Leonie removing kelp from the wreck remains.

We have less than a six-hour window to work on the site before the tide rises again and covers the wreckage. As we continue our tedious work, objects previously obscured by kelp become recognizable, like the winch pictured below before and after clearing. It was likely used to deploy and haul in the trawl net during fishing operations.

Other recognizable features include the two-bladed propeller and a boiler which would have originally been in a vertical or upright position.

Many other objects remain unidentified, even after being cleaned of marine growth. Here archaeologists inspect a heavy molded plate or fitting of unknown function.

Leonie still can manage a smile after plucking kelp from sharp metal objects for four hours straight.

As the tide begins to rise, most of the wreckage is exposed and clear of kelp. Now it will be much easier to observe and record details of the hull and other artifacts for the ongoing process of documenting this shipwreck.

We have recorded much of this wreck last year, though we have not yet attempted to document the rudder and attached steering apparatus, a complex feature which appears to have collapsed with and upon articulated transom timbers. Making detailed scaled drawings of this area will be one of our first tasks on this shipwreck this season.

The day has turned out to be a beautiful one. Once back home, the view of Minaun Cliffs beyond the bay at Dooagh is breathtaking.

Achill Island Field Report: Arrival in Westport and Clew Bay

This is the first of a series of regular updates I am writing so that those interested in the Achill Island Maritime Archaeology Project can follow our activities and share in our discoveries as we make them. My name is Chuck Meide, I am the project director, a graduate student at the College of William and Mary, and the Director of LAMP (the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program, based out of the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum). I am also an archaeologist with the Institute of Maritime History, the institute which, along with those mentioned above and the Achill Folklife Centre, is sponsoring this project. Welcome to the first update for the project!

This is the first of a series of regular updates I am writing so that those interested in the Achill Island Maritime Archaeology Project can follow our activities and share in our discoveries as we make them. My name is Chuck Meide, I am the project director, a graduate student at the College of William and Mary, and the Director of LAMP (the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program, based out of the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum). I am also an archaeologist with the Institute of Maritime History, the institute which, along with those mentioned above and the Achill Folklife Centre, is sponsoring this project. Welcome to the first update for the project!

Achill Island is situated between Blacksod Bay to the north and Clew Bay to the south. Clew Bay presents a beautiful vista, and allegedly has 365 islands, one for each day of the year. Situated on the mainland at the eastern margin of Clew Bay is the town of Westport. This became one of the most important commercial centers in the West of Ireland during the nineteenth century, especially after the close of the Napoleonic Wars. The trade at Westport was vital to the islanders on Achill. Achill boats provided fuel for Westport in the form of turf (stripped from the bogs), in exchange for limestone (which was burned to produce lime for fertilizer) and manufactured goods. Many of the ships wrecked in the treacherous waters around Achill were bound to or from Westport. Because of its proximity Achill islanders, who took every opportunity to salvage timbers and cargo from wrecked ships, had access to goods from around the world

I have decided to spend a few days in Westport, getting organized for the fieldwork ahead and conducting some background research on the maritime history of the town, which was historically interconnected with the surrounding islands. I will be staying at the home of a local family, the Shanleys, who for the last century have owned one of Westport’s oldest businesses, Shanleys Drapers. Like all the retail shops that once lined the town’s main street, this family-owned clothing shop would have been dependant on ships to bring in the materials and goods available to local townspeople.

Wandering around the town, the importance of its historical relationship with the sea is evident everywhere. This is the quay or waterfront where ships would have unloaded their cargos. Today the Clew Bay Heritage Centre can be found here, which is worth a visit for anyone traveling to the area.

Goods were stored in these stone warehouses, which front the quay and have been converted to modern shops.

These are the same warehouses seen in this old photograph of the quay, taken sometime between 1890 and 1905 (image courtesy of John O’Shea).

By the waterfront an old anchor is on display. It dates to the nineteenth century, and likely came from one of the ships entering the harbor from Clew Bay.

On Monday I paid a visit to the home of John and Sheila Mulloy. They are both local historians; John is the President of the Westport Historical Society and Sheila is the editor for their journal, Cathair Na Mart. John has agreed to spend the afternoon talking with me about the history of maritime trade on the Bay. His family ran a shipping business out of Westport and nearby Newport for the last two centuries, so he is uniquely knowledgeable about this topic.

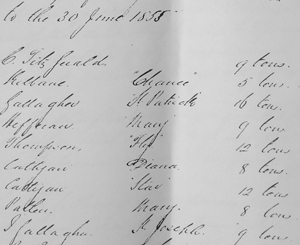

John also shared his collection of 19th century nautical charts and historical documents, which I can make a quick record of with a digital camera. Among many other things, I learn from John that Achill Islanders were very involved with the trade in and out of Westport. The following document is an 1855 record from the Westport court house listing the owners, ships, and tonnages of vessels involved in the local trade. Many of these names are of well-known Achill families, including Kilbane, Gallagher, and Patten.

Mr. Mulloy tells me that many Achill men operated their hookers (a local type of sailing vessel) as lighters. A lighter was a smaller or shallow-drafted vessel used to shuttle cargo back and forth for large ships that were too large to enter the harbor. Deep-drafted vessels, such as the Confidence shown below, would wait further out in the harbor for lighters to carry their cargo to the quay at Westport. The Confidence was a ship used by Mr. Mulloy’s family until it was confiscated by Germans in the First World War.

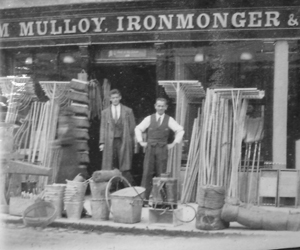

Tools and other manufactured goods brought on these ships were thereby available to local townspeople and others in the countryside at family-owned establishments such as the ironmonger and grocer’s shop owned by the Mulloys (image courtesy of the Clew Bay Heritage Centre).

Ships navigating the Bay needed the help of local seamen who were familiar with these waters. This was especially important considering the large areas of shallow water, often completely exposed at low tides, and the strong tidal currents throughout the area. Achill Islanders typically served as pilots for the outer Bay. An Achill pilot would row out in a traditional boats such as a curragh or yawl to meet incoming ships. Often a pilot would compete with another pilot in a different boat, and the first one to reach the incoming merchant ship would get paid to guide it into the inner area of Clew Bay. From there the ship would meet a pilot for the inner Bay. According to Mr. Mulloy these pilots did not compete with each other but followed a system where they took turns leading ships the rest of the way into Westport Bay. From here an incoming ship would either dock at the quay or, if it was too large, moor at an anchorage and wait for lighters to offload its cargo.

Mr. Mulloy noted that one of the last lighters to be used in the Westport trade was abandoned in the harbor, where its remains can be seen at low tides. He says it has been abandoned for a very long time, longer than his lifetime, which means it may have been used in the very early 20th century or the late 19th century. These kinds of vessels, probably locally built and operated, were a vital link in the trade that connected Westport and Achill to the rest of the world. The designs of vernacular or locally-built working watercraft have for the most part been lost to history, even though they were once so widespread they were an everyday sight. I am interested in finding this abandoned vessel if it still exists. Before heading to Achill, we will try to locate this wreck.

New Castle DE, July 06

This reconnaissance is scheduled for 16-22 July. For a copy of the research design please email david.howe@maritimehistory.org.

SHIP Field Schedule

SHIP field schedule, 2006 (always subject to weather):

29 – 30 Apr U-1105: rig buoy, inspect

06 – 07 May scan and map, Potomac River

13 – 14 May scan and map, Potomac River

20 May – 11 Jun Roper: haul, repair, paint

17 – 18 Jun scan and map, Potomac River

24 – 25 Jun scan and map, Potomac River

08 – 09 Jul scan and map, Potomac River

15 – 16 Jul Roper to Delaware Bay

16 – 22 Jul scan and map, Delaware River

22 – 23 Jul Roper to Tall Timbers

05 – 06 Aug inspect U-1105

19 – 20 Aug scan and map, Potomac River

02 – 04 Sep scan and map, Potomac River

09 – 10 Sep inspect U-1105

23 – 24 Sep scan and map, Potomac River

30 Sep – 03 Oct scan and map, Potomac River

04 – 8 Oct scan and map, Potomac River

21 – 22 Oct scan and map, Potomac River

11 – 12 Nov U-1105: pull buoy for the winter

25 – 26 Nov scan and map, Potomac River

02 – 03 Dec scan and map, Potomac River

16 – 17 Dec scan and map, Potomac River

Contact Dave Howe for underway times and locations.

U-1105 et al.

24 April. No joy yet in placing the mooring buoy on the U-1105 for the summer season. We were blown out last weekend by high winds and heavy seas.

We are looking into the acquisition of a houseboat as a “barracks barge” and floating work platform. to support a larger crew than Roper can sleep. Several cheap or free boats have been proposed. Stay tuned!

A new bacterium found in RMS Titanic

An interesting news article was published today in The Chronicle Herald. Researchers at Dalhousie University discovered a novel bacterium, BH1, isolated from rusticle specimens taken from the RMS Titanic, and have deposited the culture with the ATCC in Manassas, Virginia.

While it is not available for distribution to the community yet, an analysis of its known gene sequence data indicates that it belongs to a category of bacteria called Halomonas. Because Halomonas species are typically halophiles, they are usually found in water sources with high salinity levels, such as the Dead Sea and even within the frigid waters of Antarctica. Halomonas can also inhabit deep-sea sediment, deep-sea waters affected by hydrothermal plumes, and hydrothermal vent fluids.

BH1’s exact ”biocorrosive ability” is not clear yet. However, discovery of BH1 provides a tool for comparison and aids in identifying the potential microbes within the communities that contribute to the overall biocorrosion process(es).

The full article can be found at http://thechronicleherald.ca/Front/497160.html