INA and IMH reconned the wreck of USS San Marcos (ex USS Texas, BB-2) off Tangier Island in the Chesapeake Bay on Sunday, 6 August. The report is available in PDF format: Download file

Achill Island Field Report 14: Odds and Ends: Curragh pens, anchor stock recording, and snorkeling Dooagh pier, 12-15 July 2006

The forecast is calling for heavy seas for this week, precluding any diving, so over the next few days we are working on several alternative tasks. One ongoing objective is to continue recording the curragh pens at Dooagh pier. We would like to finish an overall plan depicting all 20 pens, the coastline, and pier itself.

They notice what appears to be an old ship fitting, now being used as part of a curragh berth. This iron band or ring has four smaller rings attached to its body, and has been embedded in cement to serve as an tie-downs for securing a berthed curragh. It appears to have once been a mast band, an iron collar with eyes and swivels for attachments which would have encircled the mast of a sailing ship. There is a long tradition of Achill islanders salvaging objects from ships wrecked or abandoned in local waters, and this appears be an example of this practice.

Throughout the day, a pod of dolphins has come in to Dooagh Bay to play, putting on quite a show for the archaeologists working at the pier. One of the locals has told us they come in to feed on the sand eels, but they certainly seem to be playing to us, jumping entirely out of the water and rolling across the waves in groups.

Later in the day, we decide that it is a good idea for our team to conduct a snorkel dive in the waters sheltered by the Dooagh pier breakwater. Getting in the water with snorkeling gear, in order to familiarize ourselves with our exposure suit buoyancy, equipment, and the local environment, is always a good idea to do before starting full-fledged diving operations. We can also test our underwater camera equipment in these more controlled conditions. Here Kevin Cullen is suited up in his new semi-drysuit, preparing to enter the water.

Our underwater camera system, which we purchased new to use on this project, has been successfully field-tested. Here is a picture of Kevin snorkeling to the rocky bottom near the pier. We all agree that this exercise has been useful for us, in advance of our upcoming diving operations. We are hoping to get some dives in as soon as the seas calm down, and to start dive operations in earnest with the arrival of our fourth team member on the 16th of June.

In the meanwhile, though, we continue to work on the shore. One of our jobs in the following two days is to record the stock of the anchor recovered from the wreck of the Sceptre, which was lost off Achill in 1841. Norine and Kevin produce an interior, exterior, and side view of one of the two anchor stock components. As we did with the anchor itself, this is done by measuring offsets from a baseline running the entire length of the artifact.

In the evening, we are pleased to see that the seas are finally laying down. Our landlord, Tony McNamara, has agreed to take us out on his boat for some fishing. Mackerel are always plentiful in Achill waters. Here Norine pulls in three fish on one line!

We also are interested in helping Tony bait his lobster pots. In the old days, lobster pots were handcrafted from wicker, and weighted with stones. They had to be checked every tide, or risk losing their catch since the wicker traps were easier for lobsters to escape from. Modern traps allow the lobstermen to check their pots less regularly, so that they won’t have to risk going out to sea in foul weather. Tony pulls up his string of eight pots, called a spillet. No lobster are caught today, unfortunately.

Afterwards, we bait the pots and return them to the sea.

We are all excited about the good weather being forecast for the next week. We had plans to dive tomorrow, on Saturday the 15th, but unfortunately the boat we had hoped to use became unavailable at the last minute. In light of this, we have contacted John O’Malley, a third generation boatbuilder from Corraun peninsula who also runs a charter boat service. He is not available for Saturday, so our first dive is scheduled for Sunday. Our final team member arrives that evening, so we are hoping that the weather holds for diving operations the entire following week.

Achill Island Field Report 16: Two Shipwrecks Under Two Lighthouses, 17-18 July 2006

Our final team member has arrived. Dr. Sam Turner is the Director of Archaeology for LAMP (Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program) and also the President of IMH (Institute for Maritime History), two of the institutions sponsoring this research project. He flew in from Florida last night to work with us for our final two weeks on Achill.

On Monday we cannot dive because our boat was already chartered for a group of sport fishermen, which is just as well because Sam will be dealing with jetlag and everyone should be in top condition for these dives, which will be relatively deep (90 feet or 26 m). Instead we stay the night at our friends the Shanleys in Westport, and allow Sam to sleep in Monday morning. In the afternoon, the crew decides to climb Croagh Patrick, the holy mountain which has been a pilgrimage site for thousands of years. Here is Sam near the top of the mountain.

The evening view of a mist-shrouded Clare island from the top of Croagh Patrick. Our first dive the following morning will take place just off this island, which is directly south of Achill.

The next morning dawns and we are in Achill. We are meeting our boat at Kildavnet pier, right next to the tower house built by the powerful O’Malley clan, whose most famous member was the 16th century Pirate Queen Grace O’Malley. Here Sam chats with our captain, local boatbuilder John O’Malley, a descendant of the original owners of the tower.

The Clare Island Fish Farm, whose facilities are located on the former site of a 19th century Coastguard station on Achill at Cloghmore, has agreed to let us use their banks to fill our scuba tanks. Their underwater salmon pens are close to the first shipwreck we will be diving on each day. Every morning we arrive early, drop off our gear at the pier, drive down the road to the Fish Farm to fill the tanks, and then return to the pier to meet the boat for our dives. Then we set off for our first dive on the shipwreck we have nicknamed the “Train Wreck.” Here LAMP archaeologists Chuck Meide and Sam Turner prepare for the first dive on this wreck shortly after anchoring off Clare Island.

The wreck is located in an anchorage under the Clare Island Lighthouse.

This light station was established in 1806 to mark the safe route between Clare Island and Achill Island. Entering Clew Bay below Clare Island was a much more dangerous route, fraught with barely submerged rocks. The area to the southwest of the lighthouse was a safe anchorage with sheltered from the prevailing winds by the bulk of the island.

The shipwreck below, unlike the Jenny at Achill Beg to the north, is intact and appears to have foundered while at anchor. It is believed that the ship was plying a coastal route and sprung a leak. It probably made it to this anchorage, where repairs were attempted, but due to the heavy cargo the bottommost part of the ship was inaccessible and, probably after hours at the pumps, she sank to the bottom in 90 feet of water. Local divers discovered the site and noticed that the ship was loaded with a cargo of what appeared to be train parts. Railroads came to this area in the 1880s, and the ship might date to this period.

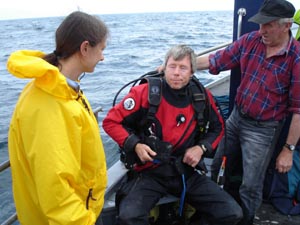

Anchored over the site, we are excited about seeing this shipwreck for the first time. Norine Carroll and Captain O’Malley help Sam gear up for the first dive.

At a depth of 90 feet, the divers will only have 30 minutes of working time to descent to the wreck and accomplish their goals. Staying any longer will put them at risk of developing decompression sickness or the bends, which is caused by a build-up of nitrogen in the divers’ bodies. We are using U.S. Navy diving tables, which help us plan safe dive times depending on what depth we will be working at. Once geared up, Sam enters the water.

The divers submerge and descend down stout line which is anchored on the bottom somewhere near the wreck. Sam’s buddy for this dive is Kevin Cullen, graduate student from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Their task for this first dive is to locate the wreck, which they will do by swimming a circle search. This is done by hammering a stake of iron rebar into the bottom, stretching a tape measure out from it and swimming in a circular search pattern, hoping to either see or snag the wreck. Here Sam has set up the search line, and is taking a compass bearing so that he will know when they have completed a full circle.

But the divers are lucky, and they come upon the wreckage almost immediately! Spread out before Sam and Kevin is a large pile of debris, including a wide variety of iron objects covered with a layer of concretion and sea growth.

Most of these objects are not easily recognizable, but the divers do think much of this sunken cargo might be train undercarriage components.

Sam and Kevin slowly explore the large, oval-shaped mound of wreckage, which is over ten meters in length.

At the far end of the wreck, believed to be the stern end, Sam notices wooden hull timbers protruding from the sand.

This certainly confirms that this ship was a wooden-hulled vessel, and closer inspection of the hull remains will help us better understand its construction and possibly let us date the vessel. There is still enough time for Sam to start a scaled drawing of the hull remains, which he will end up finishing on his dive tomorrow.

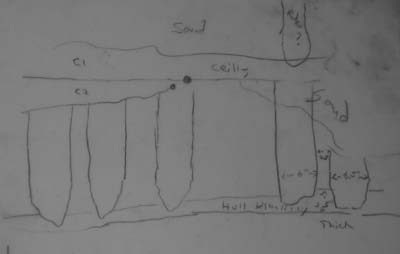

Sam’s drawing of the hull remains as sketched after his first dive.

After the completion of the first dive, Chuck Meide and Norine Carroll enter the water. Our task is to first move the heavily weighted buoy line to the wreck and tie it off to the wreckage, and then if time allows to set in a baseline over the wreck in order to accurately map its dimensions and layout on future dives. Dragging the buoy line underwater is a more difficult task than initially envisioned, as its weights are heavy and pulling over 90 feet of line and two buoys through the water column is a significant task. But the task is completed and the line is tied off to the wreck, so that we will have a direct line from the surface to the shipwreck for descents and ascents.

During our dive we notice an abundance of marine life, including several conger eels like the one pictured here. These cold-water cousins of the moray eel can deliver a dangerous bite if provoked.

Our final task is to lay in a baseline. After struggling to deal with the buoy, we have burned a lot of air and are limited on time, but we manage to use a hammer to pound in two rebar stakes, one at each end of the wreck. Between these we string a tape measure directly across the center of the shipwreck’s cargo pile. From this baseline we will be able to measure offsets from known points on the line to the edges of the pile, or to individual objects, to produce a map of the shipwreck.

After every dive, we pause on our ascent line at a depth of around 15’ for a safety stop. This allows the divers to off-gas some of the nitrogen that has built up in their system during the dive. We have decided to conduct a 7 minute safety stop after every dive on this wreck, which would be the mandatory stop time if we were to stay on the bottom for longer than the prescribed 30 minutes. Here is Norine at the safety stop.

Back on the boat, we relax for a bit after the dives. Everyone is excited after this dive. This shipwreck is intriguing, very intact, and simply a great dive! We are also pleased that we have accomplished so much on the first day of diving on it. After two dives, we have located the wreck, established a buoy line to it, begun recording the wreck, and set a baseline in place for further mapping operations. We consider this a very successful start to the investigation of this mystery wreck. But now it is time to leave Clare Island for our second dive, on the 1894 wreck of the Jenny.

Located only about 4.1 km or 2.6 miles away from the Train wreck, the wreck of the Jenny is in a completely different environment, and that has drastically affected the site formation processes that have made this a scattered spread of wreckage over a rocky, high-energy, multi-depthed bottom as opposed to an intact deep-water wreck on a flat sandy bottom. It is challenging but fun to be working on two such different shipwrecks at the same time. Because of its depth, we could not do a second dive on the Train wreck, but as the Jenny is in only 35 feet of water it is well-suited for our second series of dives each day.

Our vessel the Naomh Davnait maneuvers in the waters over the Jenny, under the sight of the tall cliffs of Achill Beg and the Achill Beg Lighthouse to the east.

Here Sam and Kevin are deploying a buoy on some more of the scattered wreckage they have identified.

From that point they are swimming a search transect using a buoy to keep in a straight line at an angle of about 310 degrees. They stretch out a tape measure to act as a guideline, because it is very easy to get lost in all of these kelp-swathed gullies even with a compass.

They then search back and forth on either side of the tape measure line, marking any wreckage they find with flagging tape, such as these pieces of partially buried logwood.

One interesting artifact they come across is an intact hull timber with a large copper-alloy bolt. The bolt appears shiny and new because of the sand with is constantly moving back and forth across its surface with the surge, effectively polishing it. This would have been a large hull timber such as a section of the ship’s keel or a frame.

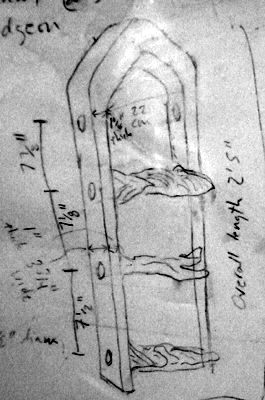

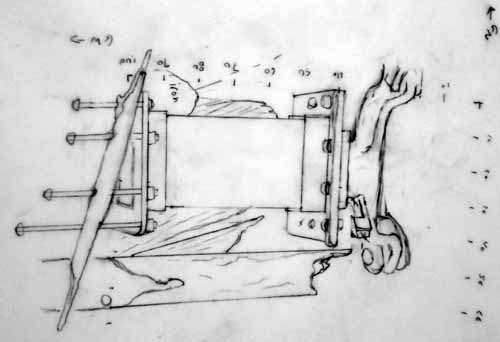

An even more exciting discovery awaits. Sam and Kevin have found a large brass fitting with wooden remains attached to its inner surface. Sam immediately recognizes it as one of the rudder’s pintles. This was a large, brass strap that wrapped around the rudder, featuring a sturdy pin on the inboard surface. This pin would have fit into the gudgeon, a similar strap that was attached to the stern of the ship, with a loop to accept the pintle pin. The rudder was hung onto the stern of the ship by these pintles, which allowed it to pivot and steer the ship. This find, located over 30 meters from the main cluster of wreckage which has been buoyed, marks the approximate location of the stern of the ship, though of course this vessel has broken up and lies scattered about. On a subsequent dive, Chuck measures the dimensions of and makes a detailed sketch of the pintle.

A buoy is tied off to the pintle so that it can be easily relocated, and so that we can see its position in relation to our other buoys once on the surface.

Chuck’s sketch of the pintle.

This is a photograph of the cove where we are diving, showing our boat at anchor near the site of the Jenny.

This detail of the above photo has been enlarged and labeled to show the boat in relation to the two buoys denoting the main cluster of artifacts, and the third buoy over the recently-discovered pintle.

Smiles are on everyone’s face after such great dives. The forecast is calling for good weather all week long, which is quite a rarity on Achill. With the acquisition of a good diving boat, the arrival of our full crew, and a week of good weather, things have really come together and we are expecting to accomplish a lot this week. As we motor back to the pier, we pass under the Achill Beg Lighthouse. It was built in 1965 to replace the light at Clare Island which went defunct when the light station passed into private hands. Our captain, John O’Malley, is not only a third generation boatbuilder but the keeper for this lighthouse. Sam and I also work at a lighthouse, back in St. Augustine, Florida with LAMP, so we are delighted to be diving on two shipwrecks under the reassuring gaze of two lighthouses.

Field Summary Report for New Castle, Deleware

IMH made a reconnaissance of the historic harbor area at New Castle, Delaware, on 16-22 July 2006 for the Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs.

Achill Island Field Report 15: First dive on the Jenny shipwreck, 16 July 2006

The Norwegian sailing bark Jenny was lost at Achill Beg Island on route to Hamburg, Germany from Morant Bay, Jamaica, on 13 January 1894. She had a cargo of logwood and a crew of ten men, all of whom survived the wrecking.

Built in 1865 at Drammen, Norway by one J. Jorgensen, she was 29 years old at the time of her sinking. Though this is rather old for a wooden-hulled sailing ship, Norwegian merchants were known for utilizing older ships to eke out profits in the bulk cargo trade. She was single-decked and measured 135’ 4” in length, 32’ 4” in breadth, and 17’ 2” depth of hold. Her home port was Christiana, Norway, her owner was A. F. Koblerup, and her captain was L. Andersen. The ship was stranded and smashed against the rocks in a force 1 gale coming in from the southwest. Pictured below is the Jafnhar, a 498-ton Norwegian bark that was probably very similar to the Jenny, which measured 492 tons.

The story of this shipwreck has been passed down from generation to generation, so a number of Achill individuals whose families come from Achill Beg Island (“Little Achill,” which is now uninhabited) remember this event. One of our friends on Achill, Jim Corrigan, told us how his grandfather, a local pilot who guided ships through the outer Clew Bay, remembered that the islanders woke up that morning to find the large three-masted ship wrecked in the cove. Jim is the one who first told us about this wreck, told us how to find it, and loaned us tanks and weights for our diving.

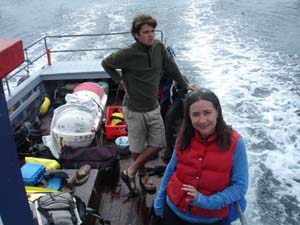

Today we are visiting the site on the wooden-hulled charter vessel Naomh Davnait, which was built and is captained by John O’Malley, a third-generation boatbuilder. John’s grandfather came to the Corraun peninsula from Clare Island, and the family has been making boats ever since.

As we round a rocky point of the island, we pass under the Achill Beg Lighthouse. It was built in 1965, to replace the 1806 lighthouse opposite it on Clare Island, which passed into private hands and ceased to be lit. Our skipper, John O’Malley, also serves as the Achill Beg Lighthouse tender.

Once in the cove, we anchor the boat and prepare to dive. Today we only have one tank for each of us, so all three of us will be diving together. Our local friend Jim Corrigan will be getting us eight tanks by Monday, so that when our full team is here we will be each diving twice a day.

The Jenny lies beneath these impressive seacliffs. This is a beautiful and dynamic setting for a dive, and the landscape is just as rugged below the surface.

The view of the Naomh Davnait with divers about to enter the water.

The divers safely enter the water and descend. Archaeologist Norine Carroll slowly makes her way to the bottom.

The divers have entered a strange underwater world of kelp-covered rocks and submerged canyons.

The bottom is no deeper than 35 to 40 feet, but the topography is dynamic and varied. The sea-cliffs above the surface continue here, and are divided by gullies and canyons, while everything is obscured by constantly flowing ribbons of kelp. The Jenny has been completely smashed to pieces by the initial wrecking process and the subsequent century of storms and heavy surges. Pieces of the ship’s hull, cargo, and fittings are scattered throughout a large area, usually hidden by kelp in the innumerable gullies that criss-cross the bottom. While this is a beautiful dive, it is immediately apparent that it will be a challenge to produce a map of the scattered wreckage. It is actually simply a challenge just to keep from being separated from our buddies while navigating this alien landscape.

It is not long, however, before we begin to encounter bits and pieces of wreckage. Pictured below are two pieces of logwood, the main cargo carried on board the Jenny. Jamaican logwood became popular in the 18th century for the manufacturing of red, purple, orchid blue dyes. Logwood is a dense tropical hardwood, and pieces of the shipwrecked cargo that washed ashore were prized by local islanders for use as thole pins or oarlocks for their curraghs or skin boats. One set of logwood thole pins were so hardy that they would outlast several sets of oars. The wood is very dense and heavy and does not float, so many pieces remain on the sea floor to this day.

The divers encounter several other pieces of logwood and other timbers, along with what appears to be a U-shaped lead tube of unknown function.

We also observe several iron knees. These are heavy rods of iron bent at right angles to serve as deck supports. We have tied a buoy to this one, so that we can easily return to this spot, which appears to be an area of concentrated wreckage.

After a 53 minute dive, we have exited the water and returned to the boat. Our mission, to locate and buoy wreckage from the Jenny, has been successful. Our dive boat is not available tomorrow, so we won’t be diving until the following day. This is not too much of a problem, since our final team member, Sam Turner, will be arriving in Westport tonight and tomorrow he’ll need to sleep off some of the jetlag. We’ll be back on Tuesday with two two-person dive teams, to return to the wreck of the Jenny and that of another, unknown ship, which sank off the coast of Clare Island to the north. Things are beginning to get exciting around here!

Achill Island Field Report 13: Arrival of Norine and Mapping the Westport Quay Wreck, 9-11 July 2006

Another crewmember has arrived on the 9th of July. Norine Carroll is a volunteer who I have worked with on a number of shipwreck projects since 1997. She currently works in the Smithsonian in Washington D.C., and has agreed to come for two weeks to work with us. Norine is an archaeological conservator, which means her specialty is the treatment and stabilization of artifacts, and she is also an accomplished diver and archaeologist as well. Norine has worked on a wide variety of shipwrecks in Turkey, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, Texas, and elsewhere. Norine was also one of the first participants in the original St. Augustine Shipwreck Survey, a project in Florida that led to the formation of LAMP, one of the research institutes sponsoring the Achill Island Maritime Archaeology Project.

Since we are coming to Westport to pick up Norine at the bus station, we plan to stay for a few days at our friends the Shanleys, and spend some time documenting the unknown wreck at Westport Quay. We spend two days mapping the layout and hull remains of this wreck. The first day it is just Kevin and myself, as Norine needs to sleep off her jetlag, but she joins us on the following day.

The Westport Quay wreck is on the foreshore, which means it is totally exposed during low tide. We have borrowed a small boat from a local Westport man so that we can drive from the quay to a point close to the wreck, and we walk out the rest of the way. The first task is to strip the wreck of the large masses of kelp which grow on its timbers.

Once the kelp is removed, the portion of the shipwreck protruding from the sediment is exposed, and we can better understand its basic layout. We can now distinguish the bow end from the stern end. Here we see the wreck from bow (foreground) to stern (background).

Its total length is about 65 feet, and it is listing sharply to the port side. In this picture the stern is in the foreground.

One of our first tasks now that we can clearly observe features on the wreck is to count and number the frames or “ribs” of the vessel. We have been able to identify at least thirty sets of frames. Frames are the thick, curved timbers that give the hull its U-shape. Frames are made up of floor timbers, which were laid over the keel and extend outwards on either side, and futtocks, which are attached to the floors and form the upward-curving sides of the ship. We have examples of both preserved on this wreck. Here Norine is preparing to tag each frame pair with pre-assigned numbers from bow to stern. This will help orient ourselves to the wreck site and aid our analysis of the hull remains.

Another important structural timber we have identified is the keelson. This longitudinal timber spans the entire length of the ship, positioned in the center of the vessel over the floor frames. It sandwiched the frames beneath it with the keel of the ship below, forming a strong framework necessary for a seagoing vessel. It can be seen in the picture above under Norine’s knees, where it runs over the frames. In the image below, Norine and Kevin are recording the position of the keelson by taking offset measurements from a central baseline which we have suspended across the entire length of the wreck near its centerline.

These measurements will later be used to plot the position of the keelson, other hull timbers, and scattered artifacts onto a master site plan.

Norine and Kevin measuring the position of a frame towards the stern in relation to the central baseline.

While Norine and Kevin are focusing on mapping the frames, Chuck is concentrating on recording the position and details of the keelson. A number of interesting features are observed, including the mast step, seen below. This large block of wood bolted to the keelson featured a mortise or hole, into which the heel of the mast was placed.

We only have several hours of work time before the tides begin to rise. Chuck and Norine, who are waterproof in their drysuits, take a few final measurements before the wreck is once again covered up by the sea.

Chuck is at the helm as the crew makes the return trip from the wreck to the quay. After two days of mapping, we have recorded the position of every frame, of the keelson, and the outline of the bow and stern assemblies. Future objectives include recording the scatter of ballast stones and ships fittings, recording specific dimensions of key structural timbers, and recording a profile of various frames to help reconstruct the original shape of the vessel. But for now we are preparing to return for Achill, where we will be spending more time on the curragh pens, recording anchors, and preparing for diving operations set to start when our fourth team member Sam arrives next week.

Achill Island Field Report 12: Mapping Curragh Pens at Dooagh Pier, 7-9 July 2006

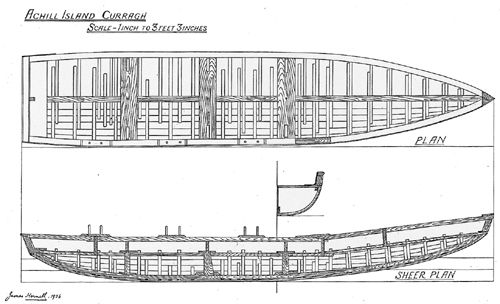

As in other colonial settings, indigenous and vernacular watercraft, notably the skin-clad curragh and wooden-planked yawl, played a central role in long-standing maritime lifeways and practices on Achill. Curraghs are the famed skin or canvas boats used for centuries along the western seaboard of Ireland. Curragh designs vary from island to island and coast to coast. In 1936 an Achill curragh from the village of Keel was recorded by the British maritime historian James Hornell.

He presumably chose a representative vessel typical of Achill construction. Since that time, the Achill curragh has undergone a series of changes, many of which were instigated by the brief flourishing of the basking shark fishery in the mid-20th century, and the increasing availability of outboard motors. These design changes included lowering the stern so that a struggling shark could not easily tip the boat, and changing the thole pins (which hold the oars in place) so that they served as a quick release for the oars, for that same reason. The curraghs today tend to be shorter and feature a square transom which will more easily accept an outboard motor. Also, today’s curraghs are much heavier and are sometimes fiberglassed.

The curraghs recorded by Hornell in 1936, and those in use today, feature wooden planking on their interior, with tarred canvas stretched over their exterior surface to make the boats waterproof. Earlier Achill curraghs did not have planking on their interior, which appears to be an innovation introduced to the island with lobster fishing. The earlier curraghs featured canvas (and even earlier still, skins) over a light wooden framework, without an interior floor of planking. This made for a much lighter and more maneuverable craft, at the expense of stability. These curraghs can be seen in this 1890s photograph of a curragh landing place at Dooagh Beach.

This photograph shows how these watercraft were an everyday part of village life, playing an integral role in the in the formation of community identity, and how visible they were on the maritime landscape. Below is a detail of this photograph, where it can be seen that these late 19th century curraghs did not have planking.

We have tried to identify as best we can the exact location that this scene took place over 100 years ago. It appears to be a spot on the beach a little to the east of the current Dooagh pier, which may be about the same age. Near this location is a gap in the rocks that almost appears to be a natural boat ramp, carved out of the landscape by glacial action. Local memory indicates that this formation was a curragh landing place, known as “Leck.” We do not yet know the meaning of this term, which might have some special significance in Gaelic. But it appears likely that the gathering of curraghs in the above photographs was near this natural formation.

Just west of this is the current pier at Dooagh, which locals tell us is probably 80 to 100 years old. We have been hoping to go diving, but the seas have been very heavy for several days—this is obvious from this picture, which shows the waves crashing over the breakwater at Dooagh pier.

Since we cannot dive, we have decided to spend some time recording the curragh pens, another of our research objectives. These “pens,” located adjacent to the pier, are storage places or berths for the curraghs, which are still used on the island. As these boats were traditionally lightweight, and this island is known for its strong winds, a secure boat storage area was vital for the islanders who depended on them for subsistence fishing. Today, throughout most of Ireland, curraghs are stored on racks. The pens on Achill are the only known such pens remaining in Ireland.

The Dooagh curraghmen appear to have taken advantage of the natural topography to carve out hollow spaces that would shelter their boats from the wind. Spoil from this activity was deposited on either side of the hollows, forming a greater wind-block, and the spaces were shored up with low stone walls, which defined the perimeter of individual pens and also helped shield them from the wind. Sometimes instead of consolidated stone walls there are simply as series of stones in a line on either side of the pen. The more modern version involves casting or using store-bought cement blocks with tie-off rings, upon which the curraghs sit and can be secured to with line.

After a quick survey of this curragh pen area we have identified at least 20 individual pens. Most of these have been abandoned, as only five curraghs are currently being stored here. Locals we have talked to indicate that these pens have been in for perhaps 100 years, which would make them likely to be contemporaneous with the historic photographs of curraghs at Dooagh beach.

In order to produce a map of the curragh pen area, we lay a baseline out along its entire length. From two datums on the baseline, we use tape measures to triangulate the positions of individual features on each pen, so that we can reproduce a plan view on paper back at our headquarters. We are starting on Pens 8 and 9, where Chuck stretches the tapes and calls off the readings to Kevin, who is recording these measurements on a sketch.

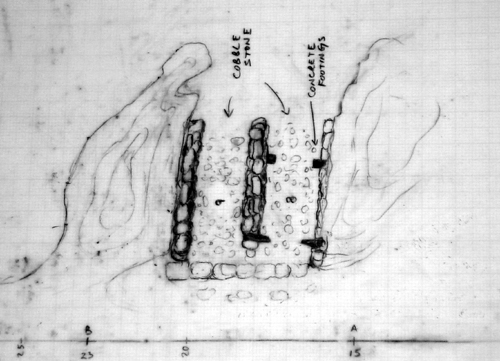

Back in the lab, Kevin produces a scaled plan drawing of Pens 8 and 9.

The preliminary drawing of these two pens, which incorporate natural hollows of the topography buttressed by spoil piles and shored up with low stone walls. The floors of the pens feature cobbles which would have kept the curraghs up off the wet ground. The pen on the right, Pen 8, has been modified by the placement of poured cement footings, which would support the curragh completely off the ground and provide iron rings to tie it down with.

The following day we are stuck inside during a gale, but the day after we return to the pier to draw a profile of Pens 8-9.

Chuck takes measurements down to various points on the structure from a leveled line suspended over the pens.

Then Kevin uses these measurements to produce a scaled drawing of the structure’s cross-section.

Adjacent to the pen area is another enclosed field with two abandoned curraghs. They appear to have been left as derelicts in their pens to rot away. A local informant tells us that one of them was a skea, a more round-hulled curragh than those built today, and that after its owner’s death it was burned and left to deteriorate by his family members. Michael Gielty, the long-time proprietor of Gielty’s Pub, has told us that curraghmen would make their own pens, which would be used solely by them, until they sold their boat or otherwise stopped using their individual pen. An unused pen could then be used by another islander to store his own curragh. In this case the curragh was left in place and has never been removed, a testament to the life and livelihood of its original owner.

Achill Island Field Report 11: Recording the Anchor of the Sceptre, 3-4 July 2006

Last year we discovered that an anchor had been raised from the seafloor around Saddle Head by some Achill fishermen in the late 1960s. We successfully tracked it down and got a look at it, but didn’t have time to fully record it. This is one of our objectives this year.

Not only was the iron anchor itself brought to the surface, but its two-piece wooden stock was as well. Both components have survived remarkably well. The anchor is about 2.5 m in length. One of its flukes has broken off, possibly during its removal from the sea-floor around 40 years ago.

Even more amazing than the anchor’s preservation is that the name of its ship was branded into the wooden stock! The letters SCEPTRE, while faded, can be clearly seen on its surface.

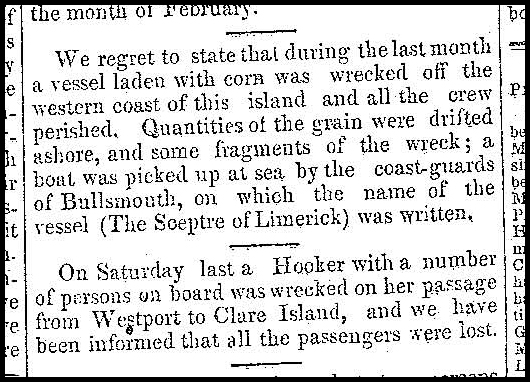

Archival research indicates there are two possible ships by this name which wrecked off Achill in March 1841. The only record of the first is a brief account of a vessel named Sceptre of Limerick reported in the protestant mission newspaper, the Achill Missionary Herald.

Courtesy of the National Library, Dublin (29 Apr 1841:48).

It is possible that this ship was named Sceptre of Limerick, or else it may have been simply the Sceptre whose home port was Limerick. The “western coast” of Achill mentioned in the newspaper description could very well indicate Saddle Head, where this anchor was raised over 100 years later.

The second candidate named Sceptre was also lost in March 1841, and it is likely that this is the same vessel called Sceptre of Limerick in the Achill Missionary Herald. This Sceptre was a 134-ton brig whose homeport was Yarmouth on the Norfolk coast of England. According to the Parliamentary records we found in the National Library in Dublin, Sceptre set sail on 27 February 1841 from Galway (west coast of Ireland, south of Achill) bound for London, but was never seen again, and “supposed lost near Blacksod Bay” (north of Achill, which could certainly refer to Saddle Head). This document also indicates Sceptre was built in 1827, making her 14 years old at the time of her loss, lists her Lloyd’s insurance rating as AE 1-40, and identifies her captain as a man named Spink.

The first step to recording this anchor is to thoroughly photograph it. This includes close-up shots of tiny details, and overall views such as the one being taken by Kevin in this picture. He is trying to approximate a plan or bird’s eye view of the anchor by getting well above it.

The next step is to position a level line along the anchors length, just above its surface.

Side view of the upper end of the anchor, showing the ring (the tie-off point for the hawser or anchor rope) and the stock keys. These projections (vertical in this picture) served to hold the wooden stock snugly in place.

Once the line is in place, a tape measure is laid out parallel to it. Kevin Cullen of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee proceeds to take measurements from the level line to record the exact shape of the anchor.

He relays the information to Chuck, who is making a scaled drawing of the anchor in both plan and side views.

We finish recording the iron anchor the following day. Afterwards, we go to Gielty’s pub to celebrate the Fourth of July, American Independence Day. Gielty’s pub and coffee shop throws the students of the Achill Archaeological Field School (who are mostly American) a Fourth of July party every year.

The party is great, complete with an American-style barbeque handled by our Achill hosts.

Michael Gielty, who used to run the pub before passing the reins to his son Alan, has arranged a special treat for us: a bagpipe band made up of high school-aged young people from the village of Dookinella performs for us. What a way to celebrate the Fourth!

Achill Island Field Report 10: Recording the Steering Assembly on the Successful Trawler Wreck, 2-3 July 2006

Last year we spend a significant amount of time recording the wreckage of the Successful, a late 19th/early 20th century fishing trawler (see Field Report 4). It is a very complex shipwreck, and we were unable to fully document it in one field season. The fact that we can only work on the wreck at low tide makes this task even more challenging. This year, we have re-visited the wreck and cleared it of a year’s growth of kelp and seaweed, in order to continue its documentation.

The rudder and steering assembly on this ship was quite complex and well-preserved. We did not have time to fully investigate this feature of the shipwreck last year, and I’m interested in spending some time recording it, to better understand its construction and operation. Kevin and I spend two days preparing for and starting a detailed drawing of this feature. Here Kevin spends some time studying this complicated feature, located at the stern of the vessel.

The rudder, seen directly in front of Kevin, consisted of a wooden blade attached by iron straps to a massive vertical iron shaft.

At the top of the rod, the rudder head was attached via a crosshead and guide-rods to a yoke attached to a barrel-like fitting which in turn was bolted to the deck. Pinned underneath this steering assembly are collapsed timbers of the upper stern.

To accurately record the details of the steering assembly, we have decided to suspend a leveled planning frame directly above the feature. This is a rigid square, 1 meter by 1 meter, with string stretched across to form a grid with 10 cm intervals. It is a useful guide when drawing a complicated object such as this. The first step is to hammer in rebar which will be used to support the planning frame.

Once the planning frame is suspended over the section of the feature which we wish to draw first, we are ready to get started. The frame has to be high off the ground because the components of the steering mechanisms rise a significant height from the seafloor. This makes the frame more susceptible to being moved by the high winds common to Achill, thus the extra rebar to help stabilize it.

Kevin uses a plumb bob to pinpoint the exact spot he is measuring, and then a folding ruler in conjunction with the string guidelines to measure its x – y coordinates. He calls these out to Chuck, who is making a scaled drawing of the steering assembly one square meter at a time.

The view looking down through the planning frame. The rectangular iron object is the fitting that was bolted to the deck. A geared yoke attached to its upper surface was acted upon by the steering wheel (no longer extant). The yoke turned a pair of guide-rods which rotated the rudder shaft, turning the rudder blade to port or starboard.

The field drawing of the square meter we finished today. While drawn to scale, it is still a rough sketch that will be refined and adjusted as we process more data in the post-fieldwork phase of the project. We are planning on continuing to use the planning frame to record more of the steering equipment, which will then be plotted on the main map of the site.

Achill Island Field Report 9: Arrival of Kevin and Lecture in Westport, 28-29 June 2006

On the 28th I’m driving to Westport to pick up Kevin Cullen, an archaeology graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. He is Irish-born, but emigrated to America when he was young, and it has been eight years since he’s been back to Ireland. He is also a diver, and will be participating in the project through the end of July.

In addition, I am going to be presenting a lecture on the maritime archaeology of Clew Bay to the Westport Historical Society on the following day. My friends and hosts in Westport, the Shanley family, suggested the community would be interested in my research, and they arranged the event with the help of Aiden Clarke of the Clew Bay Heritage Centre. As it turns out, they have asked me to be the inaugural speaker for a new lecture series established in honor of Jarleth Duffy, a prominent member of the Westport Historical Society. Mr. Duffy recently passed away, and it is obvious from talking to locals in Westport how respected he was, and how instrumental he was in the operations of the Historical Society and Heritage Centre. The lecture has been well-advertised, and we are hoping to have good attendance. Here is the announcement in the local paper, the Mayo News.

Here is the opening slide for my presentation at the new Plaza hotel. It went very well, and enough people showed up so that it was standing room only. Afterwards, lots of folks made their way through the crowd to share with me their own interest in Clew Bay’s maritime history, and a number have provided me with information useful to my research here. Events like these are important for both archaeologists and local communities, because after all it is these people’s history that I am exploring. It is worth sharing, and local knowledge always helps shape our understanding of the archaeology we do.

After the lecture, I pose for a photograph with some Westport Historical Society notables. From left to right is Sheila Mulloy, John Mayock (Chairman of the Historical Society), myself, Anne Duffy (widow of the late Jarleth Duffy), Kitty O’Malley Harlow, and John Mulloy (President of the Historical Society). They have generously presented me with a gift of a number of the Society’s published journal, which were selected to include the best of maritime history articles.

Photograph by Aiden Clarke

Kevin and I stay one more night in Westport, and then head out to Achill the following day. Things are beginning to get exciting around here, as with another team member we can accomplish a lot more work in the field.