A few days ago, my landlady Sheila McNamara brought to my attention an announcement in the Mayo News about a free archaeological tour of Clare Island being hosted by the Clew Bay Archaeological Trail (www.clewbaytrail.com). This trail, which encompasses 21 archaeological sites including megalithic tombs, Bronze Age cooking sites and promontory forts, medieval churches, and a 16th century tower house, was set up to introduce visitors to the rich archaeological heritage of the southern portion of Clew Bay. It stretches 35 km from Westport through Murrisk (west of Westport on the southern shore of Clew Bay), further west to Louisburgh, and then (via ferry) to Clare Island.

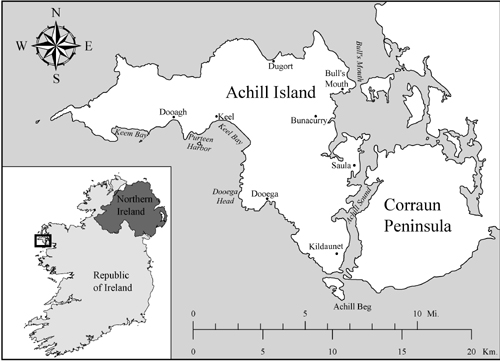

Clare Island is the largest island in Clew Bay other than Achill. Located some 5 km from the mainland, it is accessible only by boat. The dominating feature of the island is a ridge running from east to west, attains a height of 462 m at Knockmore mountain, and features vertical sea cliffs alternating with steep grassy slopes along the northwestern shore, the spectacular view I see regularly from Dooagh in Achill. Clare Island has long been recognized for its diverse plant and animal species, geological features, and archaeological sites, and was the site of a major series of scientific studies in the early 20th century.

Having long seen it dominate the horizon from the southern coast of Achill, I have always wanted to visit this island. It lies within ten miles of Achill, and the two have a long intertwined history. This archaeological tour is a great excuse to visit the island and learn more about its history, and on Sunday morning I wake up early enough to make the drive around Clew Bay to the town of Roonagh to catch the 11 am ferry to the island.

As we approach the island in the ferry boat, a squat grey stone structure looms overhead. This is a type of castle common in Ireland from the 14th through 16th centuries known as a tower house. Clare Island and the 16th century tower house that dominates the harbor are always associated with the great maritime clan of O’Malley (Ui Mhaille), and especially the famous “pirate queen” Grace O’Malley, known in the Irish annals as Granuaile (pronounced “Gran-yah-whale”).

The O’Malleys controlled a vast area of the western Irish coast from Galway to Donegal Bays, and guarded their territorial waters jealously with a mighty fleet of Irish war-galleys. “Power by land and sea” was the family motto. This tower house is one of a series built by the O’Malley clan, in order to perpetuate their control of the maritime landscape. Another, smaller tower is located at the southern entrance to Achill Sound at Kildavnet on Achill. A third tower, comparable in size to the one on Clare Island and known to have been a residence of Grace O’Malley, is located at Rockfleet on the northern coast of Clew Bay, between Mulranny on the Corraun Peninsula and the town of Newport (which is north of Westport).

Tower houses were typically designed as three-story rectangular defensible residences, featuring a vault over the ground floor and topped by a thatched or pitched slate roof. The roof was protected by a battlement parapet over the entrance, so that defenders could drop projectile weapons directly onto their attackers below. The walls were so thick that features such as staircases and garderobes (bathrooms) were encased within them.

This late medieval castle was converted in 1826 to a Coastguard and police barracks. It was at this time that the purple slate flashing was added to the two bartizans (roofed, floorless turrets). Its function as a symbol of power on the maritime landscape would have been retained in this 19th century context, though from that point on it represented British rather than Irish hegemony.

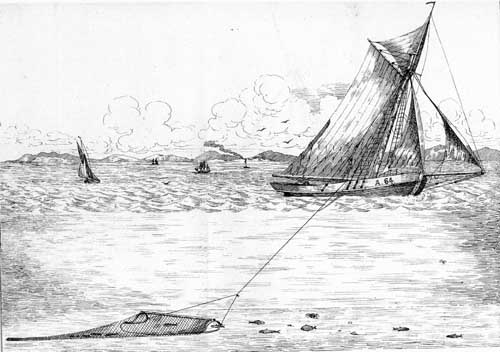

Leaving the tower, we walk along the harbor, passing a number of fishing boats including a curragh. These famed Irish vernacular watercraft have an ancient ancestry, and were originally built by stretching hides over a wicker framework. By the nineteenth century, tarred canvas was used over a light wooden framework. Curraghs are still built on the island, as they are on neighboring Achill and Corraun peninsula. Each island and coastline has its own traditional curragh styles, so those built on Clare differ slightly from those built on Achill or the Aran Islands or elsewhere.

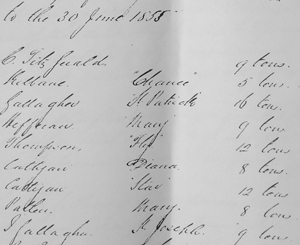

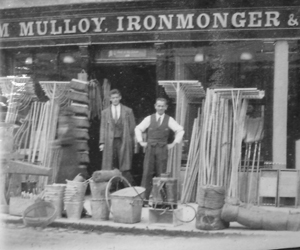

The harbor was always a focal point for maritime activity on the island. These historic photographs, taken ca. 1890s, show two views of the harbor and the tower house. Vernacular boats used by Clare islanders, including curraghs and hookers, can also be seen. The hundreds of barrels visible in these images were used to pack fish. A British government agency known as the Congested Districts Board had been set up in the 1890s to improve the local economy, and one of its projects was to establish a fish curing station on Clare.

Historic photographs courtesy of the John O’Shea Collection

After stopping in the local community centre for tea and biscuits, we commence with the walking tour of the island and visit a number of other archaeological sites. Clare Island has a rich archaeological landscape, with a wide variety of sites including one megalithic tomb, ten promontory forts, iron age huts and field systems, more than 50 fulachta fiadh (bronze age cooking sites), and a medieval abbey, which we are headed to now. Sixty-five people have shown up for the free tour, much more than expected. It has turned out to be a beautiful day.

On the horizon to the southwest is the island of Inishturk.

We come to a church known as the Carmelite Abbey. It was founded in the thirteenth century as a cell of Knockmoy, County Galway. The present building dates to the fifteenth century and consists of a chancel, nave, and sacristy.

Bronach Joyce, of the Westport Historical Society and Clew Bay Heritage Centre, points out an early medieval standing stone in the graveyard in front of the church. She is one of the tour guides.

No pictures are allowed further inside the church. This is to protect a series of medieval paintings on the ceilings and walls. They are of a style unique among medieval churches, and feature images of greyhounds, dragons, knights on horseback, bards with harps, bulls, and other animal and human figures. There is also an ornate stone tomb, adjacent to a large stone wall plaque carved with the O’Malley family crest. It is believed by locals to be the tomb of the pirate queen Grace O’Malley herself.

The tour continues as we head to the north side of the island.

Off in the distance we see the Clare Island Lighthouse. Like lighthouses everywhere, this aid to navigation was vitally important for trade and shipping in Clew Bay. The lighthouse is no longer an active beacon. It operated for a time as a bed and breakfast, and is now a private residence.

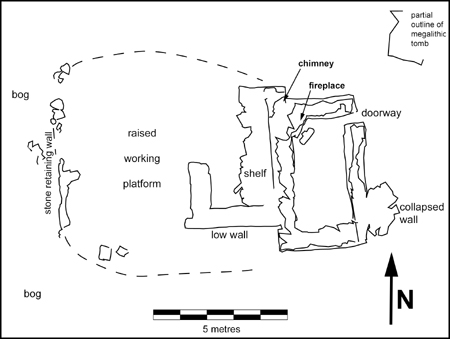

This mound and ring of stones are the remains of a megalithic tomb, built by Neolithic farmers to bury their elite. It is of a type known as a court tomb, because the stones are arranged to create an open-air court in front of the tomb entrance. It is believed that this reflects the communal nature of the funerary rituals or ceremonies that probably took place here, some 5,500 years ago. In the background are the remnants of early field walls, which might also date to this period. This megalithic tomb indicates there was a farming community on Clare Island at that time. Several megalithic tombs are also present on Achill. While examples of Neolithic watercraft (logboats or dugout canoes) have been discovered in Ireland, we know very little of early Irish seafaring. Clearly boats, likely skin-boats similar to the curraghs in use today, were used to reach these islands, but they have left no trace in the archaeological record.

The view from the tomb of the distant mountain Croagh Patrick is spectacular. Megalithic tombs were often situated to take advantages of vistas such as this, suggesting a sacred connection with prominent features of the surrounding landscape. Croagh Patrick has long been considered a holy mountain and pilgrimage site , and is today associated with St. Patrick, who brought Christianity to Ireland. Bronze age and other early sites on top of the mountain suggest that it was considered a sacred landscape thousands of years earlier.

A very short walk from the Neolithic tomb is another site, a bronze age open-air cooking site known as a fulachta fiadh. This was used by farmers 2500 years ago to boil water in what may have been a communal event. A hole in the ground, near a natural water source (in this case, a small spring), was filled with water. Then a massive fire was used to heat stones until they were extremely hot. The heated stones were continually dropped into the water until it was brought to boiling point. Meat, probably wrapped in straw, was lowered into the boiling water and cooked. Experimental archaeologists have reconstructed this process and have cooked meat in almost as little time as it would take on a modern stovetop. After use, the old stones were removed from the hole so it could be re-used, forming the horseshoe-shaped mound around the hole seen in the picture below. Some researchers think fulachta fiadh were also used as community saunas. There are 53 fulachta fiadh identified by archaeologists on Clare Island.

Around 4 pm we head back to the harbor, overlooked by the O’Malley tower house.

After four hours of walking, we have built up quite a thirst, which we quench at the local pub before taking the ferry back to the mainland.