We’ve had a few days of bad weather, and so haven’t gotten much work done. It has made for some interesting sights, though. Here the mist creeps over the crest of the mountain and threatens to engulf a holiday home below.

We’ve had a few days of bad weather, and so haven’t gotten much work done. It has made for some interesting sights, though. Here the mist creeps over the crest of the mountain and threatens to engulf a holiday home below.

The following day turns out to be nice, however. I have a friend visiting, John Bennett. He is an archaeologist who first came to Achill as a student in the Achill Archaeological Field School in 2003. John is a newly accepted graduate student at the University of Boston, and for the last two years he has participated in the ongoing archaeological excavations at Pompeii as an assistant field director. He has stopped by Achill for several days on his way to Italy for this summer’s Pompeii excavation, and has agreed to help with my research during his visit.

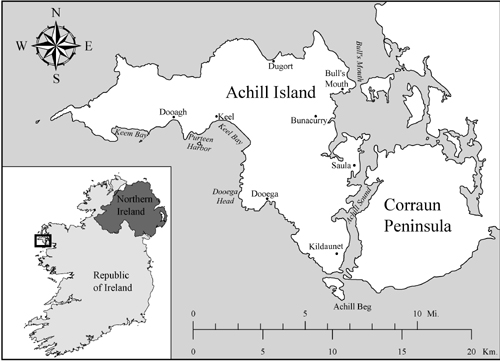

As I am interested in all aspects of the maritime landscape, not only those underwater or on the foreshore, I have always wanted to hike up to the ruins of a lookout/signal tower dating to the time of the Napoleonic Wars. It is situated on the top of a hill above the villages of Dooagh and Keel, some 194 meters above sea level, with a commanding view of both Clew and Blacksod Bays. These towers were a vital aspect of British imperial seapower in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. From its lofty perch, tower personnel could keep an eye out for enemy ships for miles out to sea, and relay messages from British ships on either side of the island, thus providing a reliable communication link between Clew and Blacksod Bays. This was done through a telegraph system using signal flags displayed in various positions to transmit coded messages.

In addition to providing a communication link for naval vessels, the tower dominated the local landscape and thus served as a prominent symbol of imperial authority overlooking the island. Residents of the Deserted Village, Dooagh, Keel, and other villages throughout the island would have seen this tower high above them on a daily basis. In this respect the structure served as a panopticon or all-seeing eye, reminding locals—who often chafed under British rule—that the authorities were always watching.

We start our hike near the Deserted Village, and make our way up Slievemore which, at 671 m is the tallest mountain on Achill. John wants to first visit a site he and another student discovered while hiking the mountain in 2003. This is a series of stone hut-like structures situated high on the mountain, overlooking Keel Bay. As they have never been excavated, their age and function remain a mystery. They could be prehistoric, they could be monastic spiritual retreats dating to the early Medieval period, they could have served as hiding places during Viking raids, they could be shepherds’ shelters dating to the later historic period, or they could be something else entirely. From a distance they are difficult to make out.

But closer up these semi-subterranean huts can be more easily discerned. The roof of the structure in the foreground has collapsed inwards, and two more huts are visible in the background. They were almost invisible when initially discovered, as they were covered with thick fern growth.

We continue the hike by turning west and heading towards the tower, which is visible on the next hilltop. As we march towards it, we pass over the Deserted Village below. The Achill Archaeological Field School has conducted excavations at a number of houses and other structures in the village since 1991. The Village, located at an elevation of between 50 and 80 m above sea level, consists of three concentrations of roofless stone houses connected by a relict roadway spanning a length of 1.5 km. It is the largest standing post-medieval deserted village in Ireland and possibly in all of Europe. Seventy-four houses remain standing of some 137 which were recorded on an 1837 British Ordnance Survey. It was occupied as early as the mid-18th century and abandoned sometime shortly after the Famine (1845-1850), its residents having moved to the village of Dooagh, probably to take advantage of its proximity to the sea. The Deserted Village continued to be occupied on a seasonal basis as a booleying village as late as the 1940s. Booleying was a practice where cattle were driven to upland locales during the growing season, to provide them with fresh mountain pasture for grazing and to allow lowland crops to mature undisturbed. Although we have learned much about the daily lives of the islanders who lived here through years of excavation, much of the history of this village, including its original name, remains a mystery.

Passing the village, we continue on the slope of Slievemore heading west. Before us, the tower (denoted by the black arrow) can be seen overlooking Blacksod Bay. It would have been visible not only from the Deserted Village but from much of Blacksod and Clew Bays.

Off in the distant expanse of Blacksod Bay looms another British sentinel: Black Rock Lighthouse.

The rugged nature of the surrounding maritime landscape is evident all around us. This is a view of the rocky shore fronting Blacksod Bay to the north. Off in the distance is the Belmullet Peninsula, which juts to the south and divides the Atlantic from the upper portion of Blacksod Bay. Sea caves like the ones visible in these pictures had long been used to smuggle goods into Achill to avoid paying customs dues, though the placement of the signal tower and Coastguard stations were designed in part to thwart this illicit activity.

Finally cresting the hill, the partially collapsed signal tower appears before us.

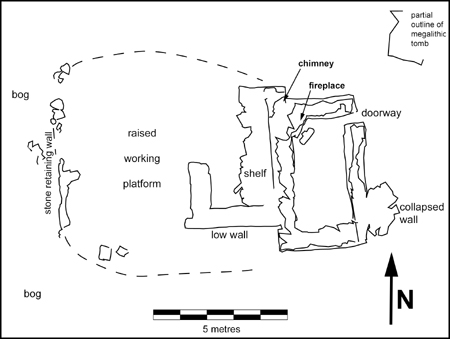

The tower is situated in a rectangular yard enclosed by the remains of a stone fence, delineating an area about 26 m by 50 m. The tower is roughly in the center of the enclosed area. This neat and orderly layout is typical of British military architecture, and can also be seen in the nineteenth-century Coastguard stations remaining on the island. Many archaeologists have suggested that this kind of imposing and symmetrical architecture was designed to impart a sense of orderliness and reinforce British authority and imperial ideology on the landscape. The low height of the wall, and lack of rubble indicating it was ever significantly higher, suggests that it may have served more of a symbolic rather than defensive role.

The tower is square, with exterior dimensions of 5.75 m by 5.75 m, and interior dimensions of 4.3 m by 4.3 m. Surrounding its remains are piles of rubble, suggesting it was once significantly taller. The north and south walls, facing the two bays, each featured two windows, though these have mostly collapsed. The east and west walls were solid.

John takes a break from measuring architectural features, and enjoys the view to the south over Clew Bay that British sentinels once shared.

A number of interesting architectural features are visible inside the structure. On the east wall was a central fireplace flanked by two inset niches which appear to have held storage shelves.

The image below shows the interior southern wall, where the remains of the two windows can be seen, along with a series of mortises (holes) in the wall below the windows which would have held wooden floor beams. These beams would have been planked to create a floor surface to walk upon, and the area beneath, at least 1.5 m in depth, would have served as storage space. A shaft in the eastern wall, to the right of the fireplace, provided ventilation to this area under the floor. Another ventilation shaft on the left side of the fireplace provided fresh air to the main chamber.

There is little evidence on the interior walls for an upper story. We would expect to find another series of floor beam mortises or put-log holes in the walls at the height of the upper floor, if there indeed was one. There is one large mortise in each wall (above and to the right of the fireplace), suggesting that there was at least one large beam crossing overhead, but it would not have been enough to support a floor, and its placement to one side, as opposed to the center, is also curious. There must have been a function for this beam, possibly to hold a ladder or suspend articles from, but it remains a mystery for now. It is also quite possible that the tower was significantly taller, and that as the upper portions of the walls are all missing the upper story floor mortises are no longer extant. The amount of rubble inside and around the tower indicate that this is a likely scenario. Fragments of roof slate found in the rubble outside suggest that its roof would have been slated, a common type of roof for this kind of architecture. Islanders’ cottages would have been thatched at this time, a cheaper but less durable form of roofing.

The picture below shows the east and south walls, depicting the fireplace (left), arched shelving niche, overhead beam mortise (left of shelving arch, and above and to the right of the fireplace), the sub-floor ventilation shaft (below shelving niche at corner), the floor beam mortises (bottom right, situated just above the ventilation inlet), and one of the two southern windows (missing its upper portion).

Looking out the southern windows, which command a view of Clew Bay, with the Minaun Cliffs on the left and Clare Island on the right. Another signal tower was built on Clare Island.

Outside the tower, in the western area of the enclosed yard, is a large depression measuring some 3 m across. Located about 12 m from the tower, it may have served as a latrine for the soldiers stationed here.

After we have recorded all of these features, we take a different route down the hill, through the old early twentieth century amethyst and quartz mining station. We make our way to the old road (ca. 1914) built for this operation. It runs right through the Deserted Village on its way to the sea, where minerals from the mine were shipped out from Purteen Harbour. These links between mountain and ocean remind us that on an island, even upland activities were part of an ongoing relationship with the sea.