Lord Dunmore’s Floating Town: Past, Present, and Future

John Oldfield and Joshua Daniel

Virginia’s last Royal Governor, John Murray, Lord Dunmore, was a controversial figure who played an interesting and pivotal role during the American Revolution. In 1775, as pressure from local colonial militia increased, he and his supporters were forced to flee his home in Williamsburg, Virginia, and his situation soon became even more tenuous. With his fleet of approximately 100 vessels – Dunmore’s “Floating Town” – he attempted to land in several locations along the Chesapeake Bay to reestablish Royal control over the colony of Virginia.

He stopped first at Gwynn’s Island, where he tried to establish a base of operations in spring 1776. After further being chased and harassed by the colonial militia, and with a crew riddled with smallpox, he fled north with his remaining vessels to the St. Mary’s River, anchoring near the mouth of the Potomac as it empties into the Chesapeake Bay. Between 15 July and 2 August 1776 his fleet attempted to find provisions in the area, under the protection of the Royal Navy.

However, when Lord Dunmore’s troops landed on St. George Island in order to obtain water, they were successfully resisted by elements of the Maryland militia. With little success on the island and no hope of regaining Royal control over Virginia, the British soon left the area. Much of the population of the Lord Dunmore’s floating town sailed south to St. Augustine, Florida. Lord Dunmore himself sailed north to New York, never to return to Virginia. Those vessels which were not sufficiently seaworthy, or for which no crew was available to sail, were abandoned or scuttled at St. George Island.

After almost 250 years, is there anything left of the remnants of that “fleet” left behind as Lord Dunmore fled Maryland’s waters? The Institute of Maritime History (IMH), a non-profit focused on the exploration, study, and preservation of our maritime heritage was recently awarded a grant by the Maryland Historical Trust to answer that exact question.

If these ships or their remnants could be located, their association with Lord Dunmore’s occupation of St. George Island would help to document one of the few Revolutionary War engagements in Maryland, and add to what is known about the withdrawal of Virginia’s last Royal Governor from both Virginia and Maryland.

IMH began its search for Lord Dunmore’s Floating Town with extensive background research at the library at the Maryland Historical Trust. The University of Virginia libraries provided facsimiles of ship’s logs that would help pinpoint the location of the British fleet’s anchorage to generate a survey area. IMH researchers searched the National Archives and Records Administration, Library of Congress, and the library of the Society of the Cincinnati for photographs, maps, and books relating to the area. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration provided historical nautical charts and the U.S. Geological Survey’s historical topographic maps provided additional data.

IMH researchers then overlayed that data with the changing conditions of the river over the past 250 years, including its dynamic, ever-changing shoreline, to best determine where the remnants of that 1776 fleet might still be today.

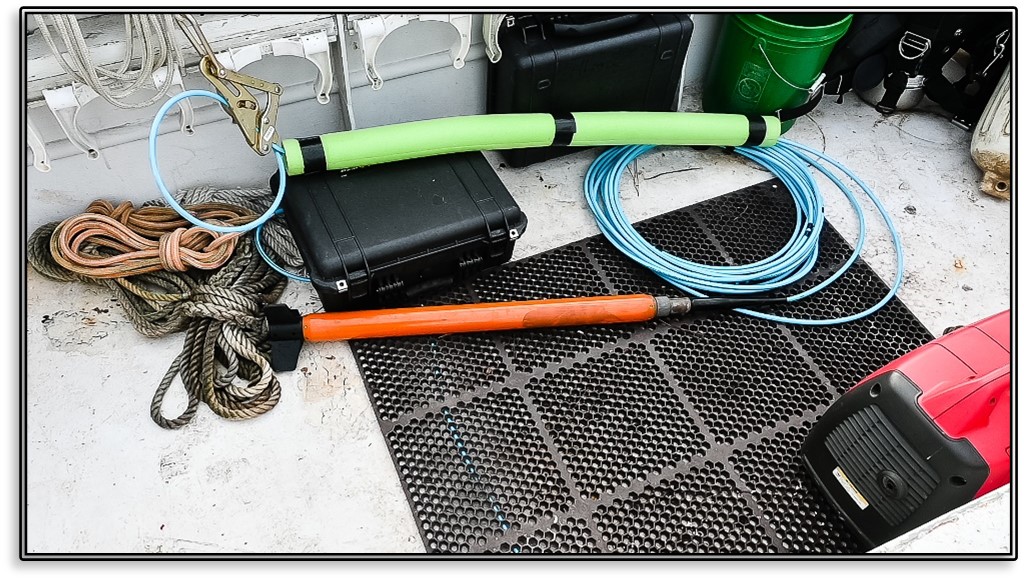

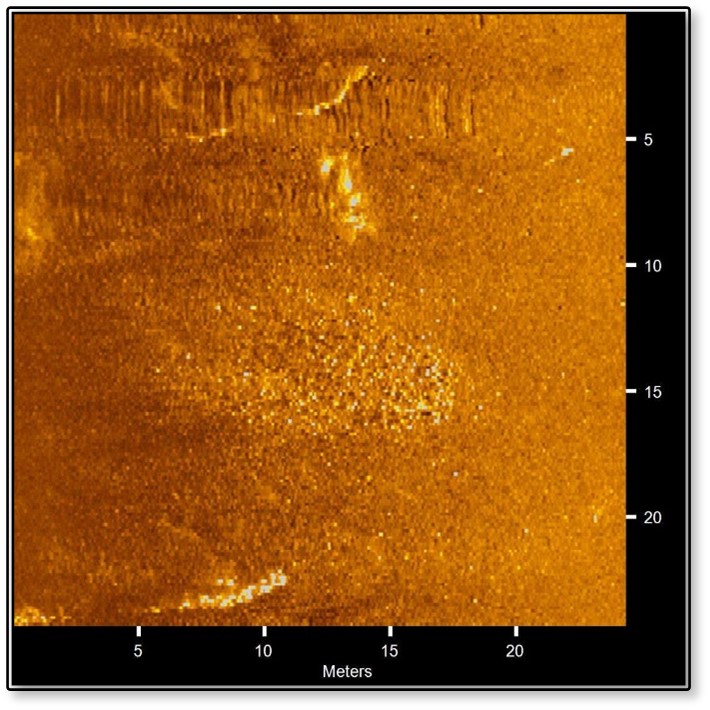

Equipped with those initial findings, IMH in 2023 conducted extensive remote-sensing at the site with a sonar and magnetometer. Although these surveys are often monotonous, with days spent carefully piloting a slow-moving boat laden with survey equipment up and down the river, the results of those surveys in October 2023 were compelling: the project identified 173 magnetic anomalies, indicating potential ferromagnetic materials (e.g. cannon, metal fasteners, bricks with high iron content, etc.) The surveys also identified 41 sonar targets, indicating objects with a surface profile above the bottom of the river.

The Institute next deployed scientific divers to the bottom of the river to locate (easier said than done in Maryland’s murky river water) and analyze many of these sonar hits and magnetic anomalies, to determine if each was man-made (cultural heritage) or natural. Could these sonar hits be remnants of the keel or planking of one of the vessels in Lord Dunmore’s fleet? Would the next sonar image turn out to be a pile of ballast stone, now visible after the vessel’s outer planking has rotted away? Could that ballast pile be covering preserved timbers from the Revolutionary War period? Could a magnetic anomaly indicate metal objects abandoned by Lord Dunmore in his haste to flee the waters of the St. Mary’s and Potomac Rivers?

IMH carefully analyzed the many targets to ensure that its scientific divers were as well prepared as possible to answer these and other questions. Ten sonar targets, some of which were associated with magnetic anomalies, were chosen for further investigation. In June, 2024, IMH sent divers down to “groundtruth” what the sonar readings had hinted at. Although diving in St. Mary’s River, and up and down the Chesapeake and its many tributaries, is often cold, dark, and challenging because of currents, divers were able to identify most of the targets in relatively good visibility, and make their determinations.

Most of the divers’ investigations unfortunately but perhaps unsurprisingly revealed derelict crab pots or trees, both common features throughout the Chesapeake Bay area. Two targets, however, stand out. The first target proved to be a scatter of angular rocks covered in oyster shell, with a greatly deteriorated crab pot in the middle of the site being the only cultural material identified during the two non-intrusive diving investigations at the site. However, this site cannot currently be dismissed as modern debris; investigations at this site proved inconclusive and further examination should focus on the use of test excavation units to verify the presence of any hull structure or other artifacts.

The final target appeared on sonar to be a symmetrical scatter of debris with two crab pots. Diver investigation located deteriorated portions of a shipwreck. The site is located at approximately 4.9 meters (16 feet) depth. Visibility on site was about 0.9 meters (3 feet) with enough ambient light to identify the remnants of a wooden framed boat. Most of the hull is buried, with about 4.5 meters (15 feet) of each side exposed. Stainless steel straps, control cables, stainless steel wire, and insulated electrical wiring were all identified on the wreck. Some of the wood was painted white with a stainless steel strip on the top. The control cables and stainless steel elements suggest that this wreck likely dates to the last half of the 20th century, and the site was added to Maryland’s repository.

Conclusion

While the remote-sensing and diving investigation undertaken by the Institute of Maritime History covered a broad area of this battlefield, no conclusive evidence of Dunmore’s presence was identified using non-intrusive methods.

However, Virginia’s last Royal Governor Lord Dunmore was a key player during the American Revolution. The waters surrounding St. George Island therefore merit additional research and investigation as the location of one of the few Revolutionary War engagements in Maryland.

This Project has been financed in part with State Funds from the Maryland Historical Trust, an instrumentality of the State of Maryland. However, Project contents or opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Maryland Historical Trust.